Nicky Sundt Jumps into fires

Photo: Kristine Jones

On July 9, 1978, Nicky Sundt joined a friend—and more than a hundred thousand self-identified feminists including Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan, and Bella Abzug—at a march in Washington, D.C., calling for an extension of the deadline for ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA).

At the rally organized by the National Organization for Women, Steinem told the crowd that “the lawful and peaceful stage of our revolution may be over. It's up to the legislators. We can become radical, if they interfere with the ratification of the ERA, they will find every form of civil disobedience possible in every state of the country. We are the women our parents warned us about, and we're proud.”

In a photo from the march—the first of many to capture Sundt protesting in the streets—she stands tall, surrounded by dozens of people clad in suffragette white. Her fist is raised and she appears to be the only one in the crowd who is aware of the camera—if not the dress code. “I didn't get the memo that I was supposed to wear white,” Sundt says, laughing. “I showed up in a striped shirt that made me look like Waldo. Can you find me?”

Sundt at the 1978 ERA march in Washington, D.C. | Photo courtesy of Nicky Sundt

Nearly four decades later, Sundt still stands out—but she’s much more savvy about how and why. On January 21, 2017, she once again joined thousands of women on the streets of D.C. for the first Women’s March, the largest single-day protest in U.S. history. People from all around the world descended upon the District—and this time Sundt, who is transgender, joined them presenting publically as female for the first time.

Although she says that transitioning in her early 60s is scary, Sundt—a former smoke jumper who fought forest fires in the western U.S. for a decade—is not one to shrink under the weight of a stressful situation. “I thought I’m going to do it now,” she says. “I'm going to be there as a trans woman at that march because it just felt like this was the time to do it. I thought I should present as who I am, as opposed to what I'm supposed to be. It was hard. I wasn’t entirely ready yet, but I’m a late bloomer.”

Photo: Kristine Jones

PERENNIAL PROTESTER

The more I find out about Sundt, the more I would argue that the appropriate plant comparison might be a perennial: one that flowers over many different seasons during its lifetime. She was born in San Francisco; when Sundt was seven years old, her family moved to the Centre-Val de Loire region of France. After their parents divorced, she and her four siblings split their time between Europe and the U.S.

Her dad worked abroad as a computer systems analyst for the U.S. government. He was a big supporter of Pete Seeger, who was blacklisted—along with his group, The Weavers—during the McCarthy era. “As soon as I was old enough to reach the record player, I was listening to The Weavers,” Sundt says.

In the ‘60s, Seeger struck out on his own to become a fixture in the folk music scene, writing and recording songs in support of civil rights, environmental issues, and disarmament. “I think I probably got some of the temperament for protest from my dad—to my knowledge, he himself never protested but that’s where his heart was.”

Photo: Kristine Jones

Sundt says the roots of her environmental activism in particular can be traced to the time she spent as a teenager in suburban Georgia. “There was garbage everywhere—people would just throw their bottles out the window,” she says.”It was such a contrast for me to see how careless people could be.” In 1972, two years after the first-ever Earth Day, Sundt organized a large protest at her high school in Germany.

When she enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley, Sundt was able to combine her interests in the environment and international policy. She wrote her senior thesis on ozone depletion, and completed her graduate degree in a new energy and resources program started by then-27-year-old professor John Holdren.

Holdren eventually served as the senior advisor to President Obama on science and technology issues, and Sundt’s career trajectory has been no less impressive. In the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, she worked as an analyst for the U.S. Congressional Office of Technology Assessment, co-authoring several of the first official reports on climate change including Changing by Degrees: Steps To Reduce Greenhouse Gases.

Sundt says people were generally receptive to the science sounding the alarm on climate change—at least in the beginning. “There were people who took me seriously,” Sundt says. “On all of these big problems there’s always someone sounding the alarm—it’s the people in powerful positions who don’t listen.”

Photo: Kristine Jones

FIRE DRILL FRIDAYS

Hoping to attract the attention of at least some of those powerful people, Jane Fonda temporarily moved to D.C. at the end of 2019 and teamed up with Greenpeace to form Fire Drill Fridays. The weekly protests took place on Capitol Hill; frontline activists spoke about environmental justice, called for an end to all new fossil fuels, and pressed for the advancement of the Green New Deal.

Sundt, who lives near Lincoln Park, joined several of the Fire Drill Friday rallies and was arrested for civil disobedience three times. She spent time in police detention with Fonda, Ted Danson, Joaquin Phoenix, Martin Sheen, Catherine Keener, Rosanna Arquette, and hundreds of others, including myself. On December 20, Sundt found herself protesting alongside Steinem once again—albeit under different circumstances than the 1978 ERA march.

“I was next to Gloria Steinem as they read her Miranda rights,” Sundt says. “I asked her if she had been arrested before and she said ‘Oh yes, but it’s been a long time.’ I asked her how she ended up here, and she said ‘Oh well, Jane [Fonda] was at my house and she made me come.’”

Fonda, a notoriously persuasive and prolific activist with a history of championing LGBTQ issues, made a positive impression on Sundt—a feeling that appears to be mutual. At a post-protest dinner with fellow climate experts, Sundt says that Fonda immediately enveloped her in a big hug and they later shared a piece of carrot cake for dessert.

Not only was Sundt surrounded (and accepted) by the revolutionary women Steinem had been warned about—but now Sundt was officially one of them too. “The women were all amazing,” she says. “It was scary, I had never been arrested before—and now I have a police record. But I’m proud of it.”

Photo: Kristine Jones

WHERE THERE’S SMOKE

Sundt’s police record may be relatively short, but her resume is not. In the late ‘70s, Sundt started firefighting for the U.S. Forest Service; she is certified as a parachute rigger, squad boss, and tree faller. “It looked like a blast,” Sundt says of smoke jumping. “But it was absolutely terrifying. The first time I jumped, I forgot to do the roll and landed on my feet. My boss said ‘You should have broken both legs.’”

After a decade—and a few more injuries—Sundt decided it was time to hang up her parachute. She stayed in the District, wrote and edited several newsletters and magazines devoted to climate change, and worked as a communications director for the U.S. Global Change Research Program Coordination Office.

The first national climate assessment came out just as the Clinton/Gore administration was departing, which Sundt calls “really bad timing.” She says there were forces within, and outside of, the Bush/Cheney administration that wanted the climate assessment buried—but that she “found all sorts of creative ways to make it really hard for them to do that.” These so-called “gatekeepers” were censoring reports, altering scientific documents, and watering down the language to make climate change seem like a minor threat.

“Suddenly the powerful people recognized that this was no longer an academic issue or a science issue—that this couldn’t be confined to perpetual research any more and it was starting to pose a threat to their bottom line,” Sundt says.

Photo: Kristine Jones

Sundt, whose ex-wife works with infectious diseases, might joke that they raised their daughter in a “disaster household,” but her bottom line is pragmatic. “My approach is rooted in my own personal experience which is, if you’re focused on preventing stuff from happening, then you’re going to feel like you’re losing,” Sundt says. “Things are not getting better—climate change is permanent, the planet is going to continue warming, we’re going to see continued disruption, and the magnitude of these disruptions is going to grow.”

Sundt understands—both in her own life and in regards to the climate crisis—that you can’t turn back time. “The question is not ‘Can we get back to where we were?’ but ‘What are the alternative futures we can have?’” she says. “And the alternative futures are very different depending on what we do now.”

But one thing is certain: “You cannot have an unfettered energy industry and an effective climate policy,” Sundt says. “It requires massive government intervention in the energy market and there’s no way around it. The people who have the power to change things aren’t suffering the consequences of their actions and they don’t have to listen. They’re not even hearing you because you’re not in their orbit—but also they are choosing not to hear you, particularly given the implications.”

It’s been almost a decade since Sundt wrote an article published in the Huffington Post calling on politicians to “Wake up, smell the smoke, and act on climate change.” With each passing year—increasingly full of super storms, devastating wildfires, and rising temperatures—the implications of government inaction become more and more clear.

“Alas, many of our elected representatives in Washington are napping on the fireline,” Sundt wrote in 2012. “They need to wake up and smell the smoke. They need to take climate change seriously. They need to help Americans cope with the impacts we’re feeling now, and prepare for the impacts that will grow more disruptive in coming decades. And they need to reduce the risk of catastrophic consequences from climate change in the longer-term through policies that help us reduce our dependence on fossil fuels.”

Photo: Kristine Jones

NAPPING ON THE FIRELINE

In 2016, Sundt was napping on her own fireline: while working as the Director of Climate Science and Policy Integration for the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), she woke up and smelled smoke. Thanks in part to therapy, the internet, and the popularity of trans celebrites like Laverne Cox, Sundt finally realized that she was transgender.

When she was a kid, Sundt says she begged her mom to let her wear dresses. When her mom eventually acquiesced, Sundt recalls being ridiculed by her peers: “I realized this was not an experience I wanted to go through again.” In the early ‘90s, Sundt got married and started a family; she stopped fighting physical fires and started fighting mental ones.

“So many of us are forced to spend some portion of our life trying to be something that we’re not,” she says. “It’s so hard. We just did what we thought we were supposed to do and it creates all this stress. You think, ‘What’s wrong with me? Is this normal? Why am I feeling this way?’ You just kind of keep it to yourself.”

Sundt says she didn’t even know the word “transgender” existed until fairly recently. But once she did, “it was such a relief—realizing what you are—understanding yourself and then getting other people to accept you for what you are and being able to live that life,” she says. “I just thought ‘I can’t live my life as something else.’ I mean what a pity. What a wasted life if you can never actually be who you are. I thought, ‘I can’t live this way anymore. I can’t deprive myself of my identity.’”

Photo: Kristine Jones

Before she had even decided what her own alternative future would look like, Sundt helped change the WWF’s discriminatory insurance policy to cover transition-related expenses. “I just knew that I wasn’t going to hide it and that I was going to be an advocate for trans people, including myself,” she says. “It’s hard if you don’t fit—you’re left to make your own road map, which makes us stronger and more resilient. But, of course, I would have preferred not to have had to go through some of it.”

Because she started her transition later in life, Sundt realizes that she “just can’t pass for a lot of people, but that’s OK,” she says. “I’m trans, and that’s what I am. I’m not trying to be anything else. I’m just a trans person. I want to present the way I feel, but I don't want to change for other people.”

THE ‘WORST POSSIBLE THING’

Sundt left the WWF in the midst of her transition, hoping that her first job presenting as female would be within the Hillary Clinton administration. Then of course on November 9, 2016, “the worst possible thing happened.” During the campaign season, trans people had become a hot button issue for Republicans. “They were using us to stir up their base,” Sundt says. “We became like flag burning or prayer in the schools or abortion—it was now ‘trans people are in your bathrooms!’”

Photo: Kristine Jones

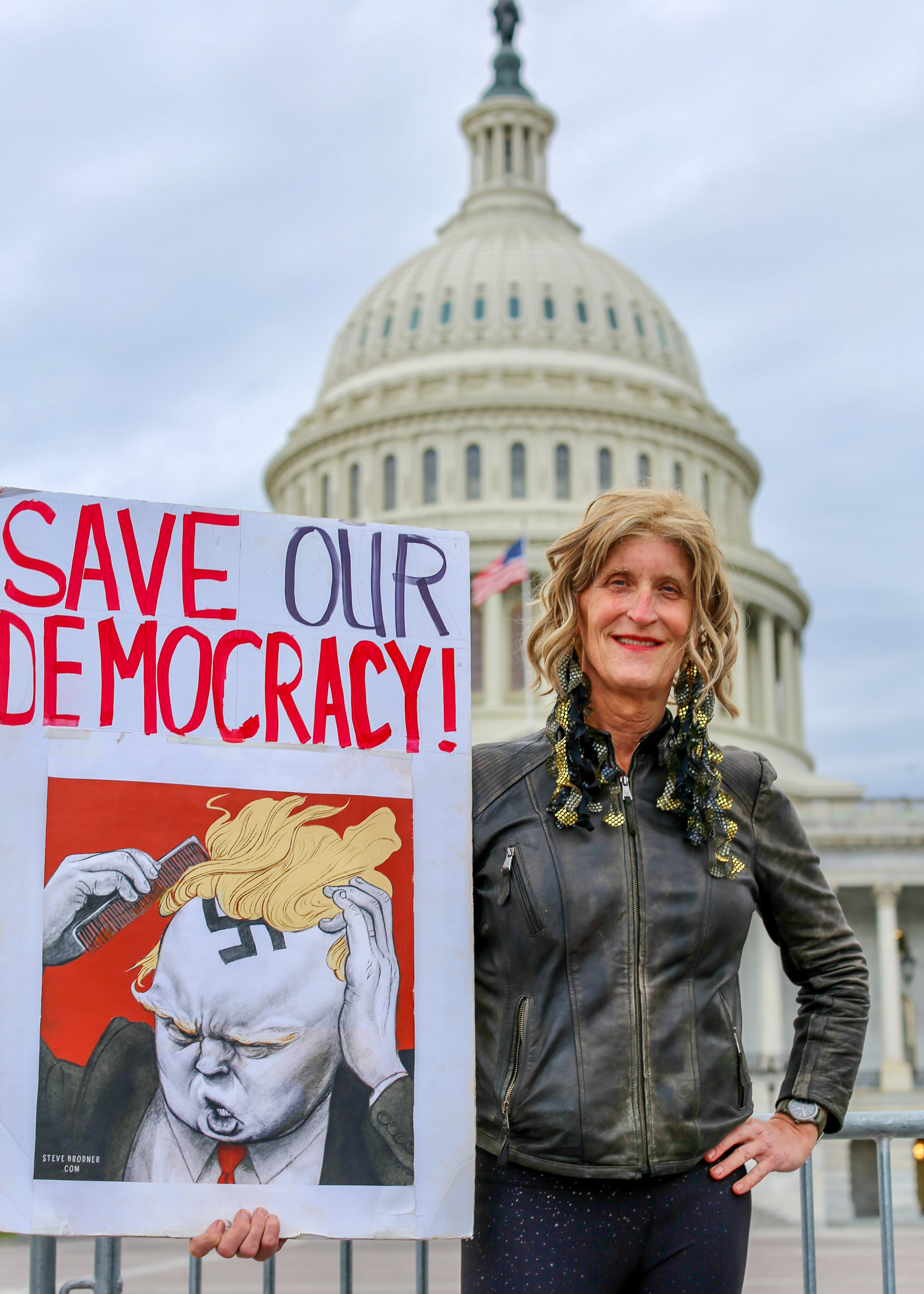

Sundt tried to channel her energy positively while working with trans groups and candidates—and into the streets. She estimates that since Trump took office she’s been to more protests in the last four years than in her previous 60. “I think that for all the negative stuff that Trump has done, he has done a lot to galvanize groups to act,” Sundt says.

Although Sundt says she was taught by her parents to care about people, she admits that “it’s so much easier to tear things apart than to build things.” As she watched the Trump administration ignoring or actively dismantling so much of the climate policy she had helped create over the years, Sundt felt largely powerless. Living in D.C. without proper representation in Congress limited her options further. “It just seemed like street protests were one of the few things we could do,” she says.

She says that doing so as a woman has been eye-opening in a lot of ways she didn’t expect. “You start seeing patterns of behavior that were invisible to you before,” Sundt says. “I’ve become more sensitive to the different perspectives that people have depending on their race, their religion, their ethnicity—all of those things can make people see the world very differently.”

Photo: Kristine Jones

But Sundt knows instinctively that no matter how stark our differences, meaningful change can only be achieved by focusing on what connects—not divides—us. “We have to sew these different movements together into a coalition that deals with a whole range of concerns,” she says. “If we’re all pushing and pulling in different directions, we’re too easy to defeat. We need to unite, we need to focus and accept that maybe our issue is not going to the top one this time.”

In her own life, Sundt tries to practice what she preaches. She says she tries to be a “good ambassador” for the trans community and prefers not to scold people who may misgender her. She encourages people to ask her questions, and tries to be cognizant of the times when she should speak out, or step back and let others have the spotlight.

“I believe strongly in the power of example and trying to find a positive way forward, not letting fear dominate what you do, and in being generous,” she says. “When I go to a protest I try not to be angry, I try to make people laugh. You can have a good time and also change the world while you’re doing it—we can all be happy warriors.”

Photo: Kristine Jones

HAPPY WARRIORS

The idea of a “happy warrior” may seem contradictory, but Sundt sees no reason why social justice can’t be served with a smile. Her statement earrings and colorful leggings make her easy to spot on daily bike rides or while she’s walking her dog, Blue, around Capitol Hill. During the past few months she passed out coupons to friends, each redeemable for a free hug once the pandemic is over. When she went to the police station to post bail after her third arrest with Fire Drill Fridays, Sundt brought along a ‘Get out of jail, free” card from Monopoly. She asked the officers “Is this good here?” (they said no). At the most recent Women’s March, Sundt wore a feathered face mask and carried a sign adorned with tombstones that read “Scare ‘em on Halloween. Bury ‘em on election day.”

Whether or not she has always embraced it, Sundt knows that she wasn’t made to blend in. Drawing on her strengths as a communicator, Sundt crafts simple and evocative protest signs; she knows how to position herself in front of a camera (or climb a light pole) and knows how to provide journalists with the perfect protest visual. When Sundt got arrested with Danson and Fonda, her dad called her from France; he had seen her photo in a local paper.

“To me, there’s no point in making a sign if the only people who see it are the people at the protest,” she says. “You want to entertain people and make them laugh but ultimately what you really want is for your message to be broadcast everywhere.”

Photos courtesy of Nicky Sundt

She may smile—or even sparkle—while she says it, but Sundt has always been serious about the climate crisis: “We no longer have the luxury of time,” she warns. “We need to disempower these people who are standing in the way so the rest of us can get things done. That means voting, knowing what your representatives are doing, putting pressure on them to do what they need to do, and keeping white nationalists, climate deniers, out of our politics so we can get shit done because we’re out of time. We are fucking out of time.”

As such, she sees this election as a “framing event,” something so monumental that it shakes people to their core. “These opportunities don’t come that often and you have to be ready for them,” she says. “But if you’re ready for them—and you take advantage of them—you can get lasting change.” After taking four years off from focusing on her career, Sundt is ready to go back to work—hopefully in the Biden/Harris administration, she says.

But no matter what happens on November 3 and beyond, Sundt says she’s not yet ready to retire; there are simply too many ideological fires that need to be fought. And she knows better than anyone that whether you’re dealing with climate change—or questioning your identity—sooner or later the time comes when you have to stop napping, wake up, and jump into the fire.

“It’s never too late to start,” Sundt says. “You can make a difference. Every movement has started with a small group of people and sometimes they take off and sometimes they don’t. But you don’t want to look back on this period and say—if you’re talking to your grandkids or just to yourself—‘I didn’t do anything. I didn’t do what I could have done.’ So do what you can, when you can, and how you can. There’s always something that people can do.”