Justin Dawes gets into necessary trouble

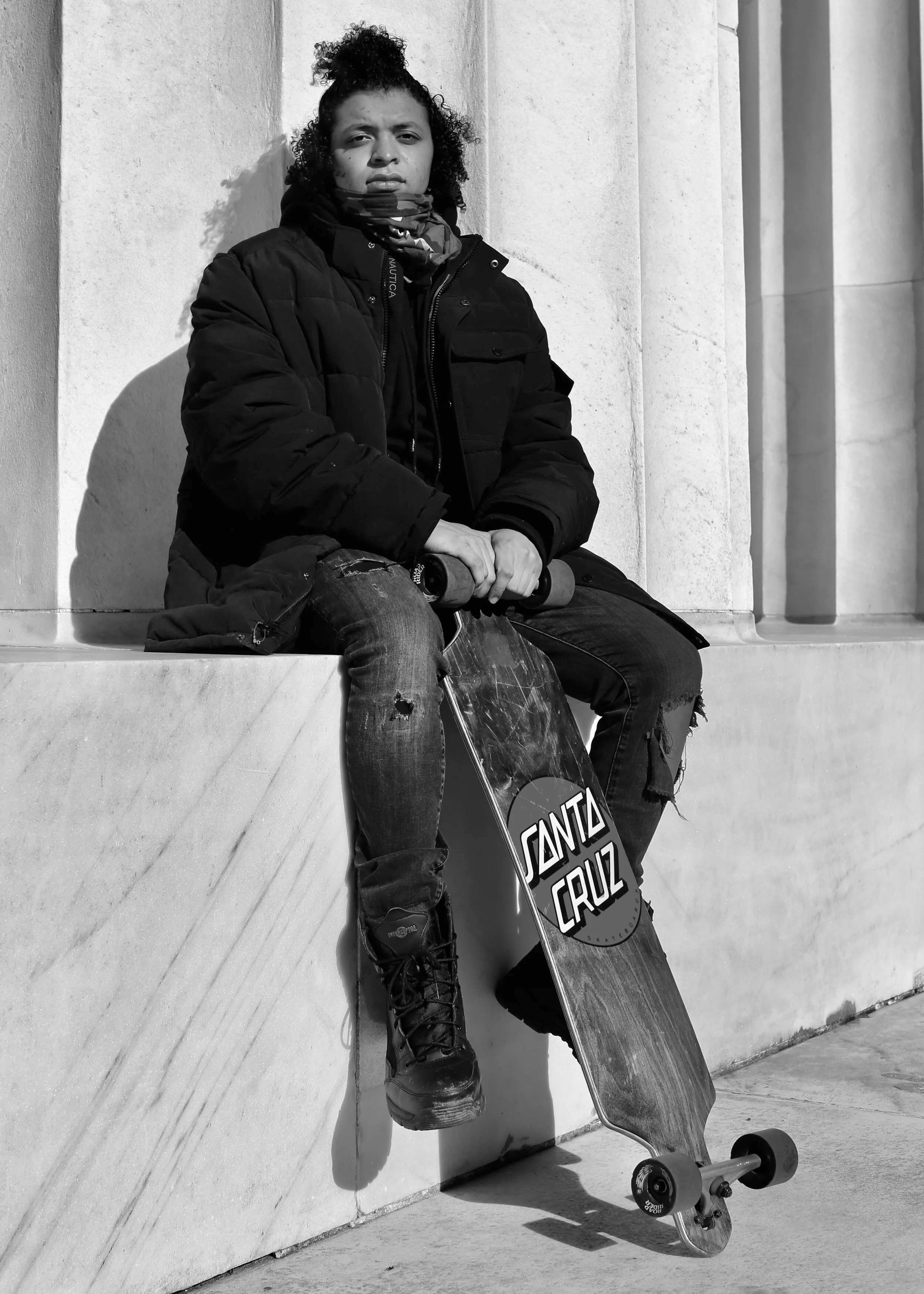

Justin Dawes and his longboard. | Photo: Kristine Jones

Justin Dawes, an activist and second-year student at New England Law | Boston (NELB), has been arrested once in the eight months since he co-founded D.C. Protests last summer. On August 14, 2020, he was taken into custody in the Adams Morgan neighborhood—but his arrest (along with most of the 40 others that night) was “no papered” the next day, meaning that the charges were dropped.

On January 8, a Boston news station erroneously reported that Dawes had also been arrested in the Capitol riots and charged with “assault on a police officer, crossing a police line, and resisting arrest.” He says he was nowhere near the Capitol on January 6; WHDH 7News issued a correction, but a few days after the siege, Dawes received a call from his school’s registrar. During a call that lasted just 53 seconds, Dawes was dismissed from his law program.

Although failing to disclose his August arrest was not the only reason cited for his dismissal, Dawes says that he was still waiting on two final grades when he was told he didn’t meet his program’s GPA requirement (which he says had been in flux due to the pandemic). Thanks to the support of a few of his teachers, Dawes is appealing the school’s decision, but as a result, he is unable to enroll in classes this spring and is looking at finishing his law degree elsewhere.

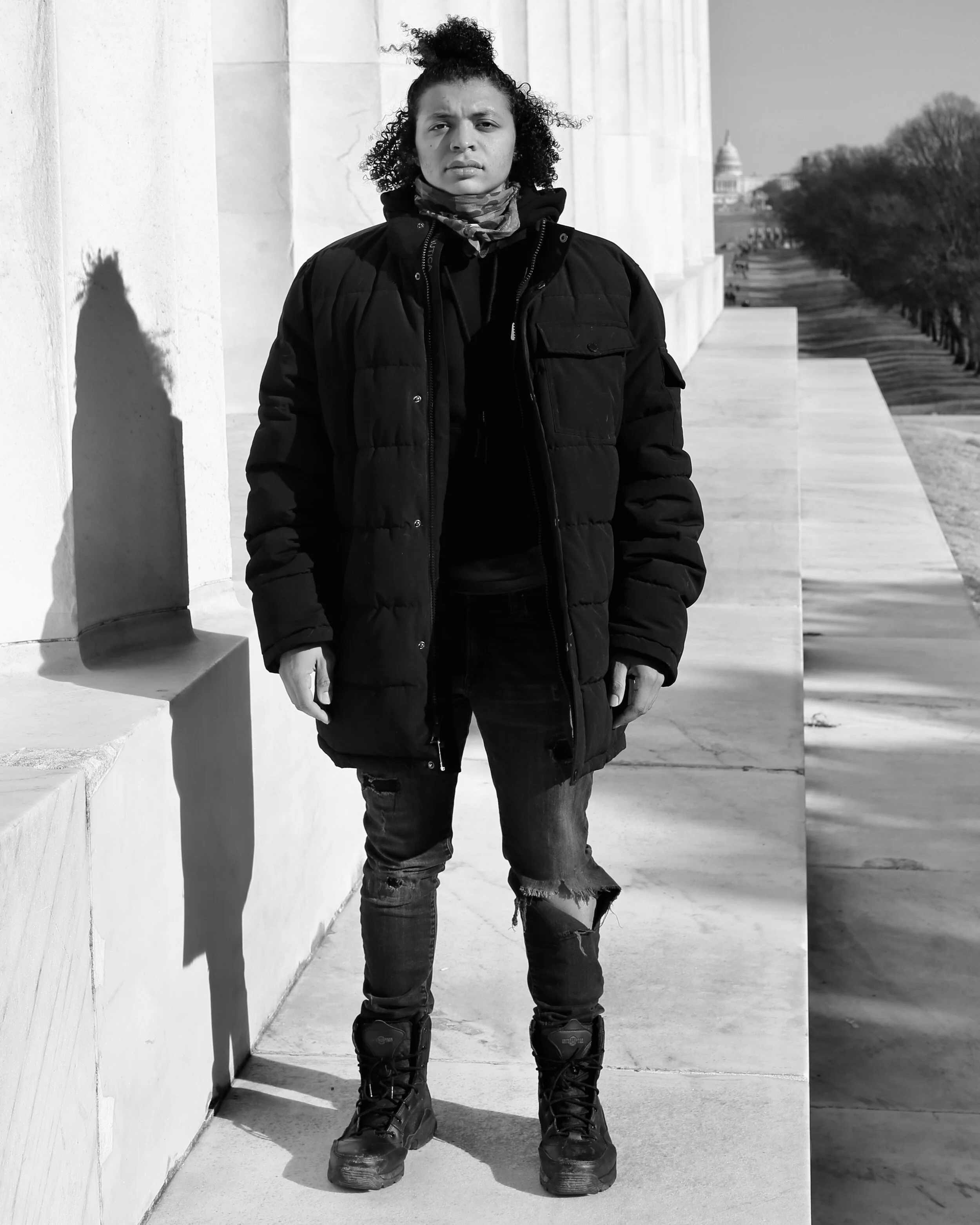

Photo: Kristine Jones

Getting arrested in the U.S. has never been a one-size-fits-all experience. It should be obvious by now to anyone paying attention that those who are white, or simply just white enough, often have drastically different encounters with law enforcement than those who are neither. The list of Black people who, by some combination of luck and skill, managed to not only survive, but to thrive after one or more arrests is painfully short.

A notable exception may be Congressman John Lewis, who was arrested at least 45 times during a long life devoted to activism. He served in the House of Representatives for decades and in the end, was admired for his rap sheet. But honors seldom make up for the horrors that precede them. Over a lifetime committed to what he called “good trouble,” Lewis was no stranger to the sting of tear gas. He nearly died when he was just 25; his skull was fractured by state troopers during what was supposed to be a peaceful march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. He had the photos—and lifelong scars—to prove it.

In an Instagram post, Dawes writes: “It’s become the unfortunate reality that while fighting for Black futures, my own has been jeopardized by a lack of understanding and support from my law school.”

D.C. PROTESTS

A cloud of tear gas was still lingering just north of the White House on June 1, 2020, when Dawes and a few others co-founded D.C. Protests. He says he and his friends had been sitting in Lafayette Park when U.S. Park Police and National Guard troops began violently clearing the plaza in front of St. John’s Church ahead of Trump’s now-infamous Bible photo-op.

Dawes, who lived in Virginia at the time, had been surveying the protests while skating with friends around the Capitol. When chaos broke out around them in Lafayette Park, Dawes says it was his first time joining, and somewhat accidentally, leading a protest: “I didn’t know what to do so we just started marching.”

When someone asked the nascent group, “Who are you?” they made an Instagram page that same night—and a grassroots organization dedicated to “confronting the injustices that disproportionately affect Black and Brown communities” was born. The group grew quickly; they continue to march and organize mutual aid efforts with regularity—often co-led by Dawes threading through the crowd on his ever-present longboard.

D.C. Protests may have started with a flashbang, but their marches quickly became a Saturday staple. Meeting in Malcolm X Park (also known as Meridian Hill) in northwest D.C., the group marches for miles; the route varies, but their message does not: “You can’t reform the police,” Dawes says. “We just have too many cops.”

Photo: Kristine Jones

Angela Davis has said, “Prisons do not disappear social problems, they disappear human beings.” And while calling to “defund the police” has become a political hot potato, abolition is a well-researched and nuanced movement with real potential to create a more mutually beneficial society. Dawes says his group has tried to humanize the insidious evils of systematic racism while also stressing the importance of grassroots politics.

“Your mayor or city council person can do a lot more than you might think they can,” he says. “If we invest back into the community—into schools and education, where it counts—we won’t need the police.” Abolition may be a hard concept to grasp, but in theory, it would happen naturally if we properly allocated resources to the point where people can truly rely on one another—instead of on police departments that often have no real connection to the communities they serve.

Similar protests have played out in streets all across the country since last summer (and on and off for most of our country’s history). Dawes and others criss-cross through disparate communities—shutting down bridges, tunnels, and highways in the process—engaging with anyone who will listen (and perhaps, especially those who do not). Dawes says the group intentionally plans their itineraries to take them into high traffic areas. Georgetown, an affluent neighborhood popular for brunch and other weekend activities is a favorite. “We just try to get people to pay attention,” he says. “We’ve received mixed reactions—people either join the march or try to fight us.”

Photo: Kristine Jones

TACTICAL VESTS AND ARRESTS

The trench coat and backpack worn by Lewis on Bloody Sunday may have become iconic—but they didn’t offer much in the way of protection when he found himself on the receiving end of a nightstick. After just a few weeks of protesting, during which the police response became increasingly erratic and violent, Dawes began wearing a camouflage tactical vest.

Like most people I encounter during the countless Black Lives Matter and other protests I attend during the pandemic, Dawes’s nose and mouth is almost always covered with a grey, red, and white bandana emblazoned with jagged teeth—reminiscent of the painted nose of a WWII fighter plane. For a few weeks in the summer he wore an eye patch. And the longboard? “I’ve just always loved longboarding,” Dawes says. “Plus it’s an efficient mode of transportation.”

Photo: Kristine Jones

If it seems as if Dawes is dressed for war, it’s because he is: Almost immediately after forming D.C. Protests, “There were threats to our lives,” Dawes says. And Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) officers—whose slogan is “We are here to help”—seemed all too ready to deploy rubber bullets and tear gas on the non-violent protesters.

Far from helping, Dawes says, “The police have always made me feel unsafe.”

After George Floyd was killed by a police officer at the end of May—and D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser designated the space between Lafayette Park and St. John’s Church as Black Lives Matter Plaza— “people were just always out,” Dawes says. But as interest in the protests grew, so did pushback from the city’s dozens of police departments. As time went on, the “police ramped up and got a lot more violent,” Dawes says. “You’d get shoved in the back of a protest if you weren’t moving fast enough—every month it would intensify.”

On the night of August 13 (and early into the morning of the 14th), Dawes says that tensions were particularly high. Police and protestors found themselves in a “huge cat-and-mouse game” that resulted in 41 arrests. D.C. Protests had begun to preface their weekly marches with a warning: “We told people to write the National Lawyer Guild’s number on their arm, explained how aggressive the police could be, and tried to tell people what to do and what not to do,” Dawes says.

Photo: Kristine Jones

Five months later, Dawes struggles to remember the exact details of the events leading to his arrest—only that it was chaos. He does remember the police, who regularly followed protesters through the streets, rushing forward into the crowd for seemingly no reason. They pushed surprised protesters out of the way, kettled others, and began making arrests. Eventually, Dawes says, someone told the crowd they were free to disperse; as he was running away, he was tackled and handcuffed. When he asked why he was being detained, the officer said he had crossed a police line—the same one that Dawes had just been told no longer existed.

‘SUCK IT UP’

On the Saturday immediately following the arrests, I am one of a large group of protestors departing the hilly park for a late afternoon march. Cleared of all charges and clutching a portable speaker, Dawes nimbly navigates a sea of moving bodies like a cat weaving through a crowded shelf: with confidence, precision, and only the occasional minor misstep. We’ve barely started down a steep hill when the group grinds to a halt. Dawes’s longboard has gone rogue; it rolls beneath several cars before nearly disappearing into a storm drain.

Several comrades spring into collective action and Dawes’s beloved board is spared the sewer. It’s the first time I see him smile. Seeing a smile in the summer of 2020 is rare; having a reason to smile might be even more so—especially, I suspect, for someone like Dawes: politically engaged, and not white.

Photo: Kristine Jones

Dawes says that when he got into some not-so-good trouble as a kid, his lawyer simply told him to “suck it up.” Looking around the courtroom packed with white people in positions of power, Dawes vowed to one day be the one giving—instead of receiving—legal guidance. “White people were making decisions for me and about my life,” he says. “I just really wanted to see someone in the legal field that looked like me.”

Like many others, Dawes was horrified by the graphic video of Floyd’s grisly murder. This was one instance where he would have preferred to see less representation; it wasn’t a big leap for Dawes to imagine himself in Floyd’s position. “Seeing someone like me die in the street was really scary to see,” he says. “We needed to be out there. I don’t want the next person to be me or be someone I know.”

When his classes at NELB went virtual due to the pandemic, Dawes says he was forced to reconsider how he was using his downtime. “When I got sent home from law school, I thought “I could be doing better things with my life.’”

Photo: Kristine Jones

MUTUAL AID

Although they were initially motivated by tragedies that captured national attention in 2020—including the murders of Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and countless others—Dawes says they started D.C. Protests primarily as a way to keep the local community safe. As the summer progressed, they began to highlight local victims of police brutality or gun violence, creating memorials and incorporating candlelight vigils into their regular marches.

Emulating similar collectives such as They/Them, D.C. Protests began to support and expand upon existing mutual aid efforts around the city. In the beginning, Dawes says that the group would collect monetary donations, stop the march at a Whole Foods, and distribute whatever they could buy to communities in need. “We wanted to show people how easy mutual aid is,” he says.

Every Saturday, groups working under the umbrella of FTP Mutual Aid build and winterize tents for unhoused communities, cook, transport, and serve hot meals, and distribute donated supplies such as clothes, diapers, and other necessities. Dawes says that the mutual aid efforts have become especially important during the winter amid an ongoing pandemic; members of “communities that are overlooked and restricted by governmental red tape” have come to rely on the weekly pop-ups in Dupont Circle.

Mutual aid efforts in Dupont Circle. | Photos: Kristine Jones

In an open letter to NELB, Dawes writes that he himself “began facing housing insecurity at the onset of the fall semester. This not only altered my sense of stability, but also affected my access to stable internet connection in order to complete assignments and attend class. Despite this hardship, I remained determined and maintained a nearly perfect attendance record.”

When he reached out to the school for support, he says they “scoffed” at his problems.

“In such challenging and discouraging times, the administration’s solution should not be to turn its back on its students,” he writes. “I am of the opinion that compassion and an extension of trust and good faith would result in a prodigious class of noteworthy lawyers.”

Wherever he completes his degree, Dawes is still committed to fulfilling his childhood dream of becoming a noteworthy lawyer. Drawing upon his own experiences, Dawes says that he simply “wants to help people,” and intends to do so by practicing criminal defense law. Instead of being in conflict with each other, Dawes foresees his legal career informing his organizing work, and vice versa.

“You don’t have to know all of the ins and outs [of the system] to dismantle it, but it helps to be realistic,” he says.

Police block alt-right groups from Black Lives Matter Plaza in December 2020. | Photo: Kristine Jones

NECESSARY TROUBLE

For activists and other targets of alt-right fascist groups like the Proud Boys, the reality on the streets of D.C. had been grim long before the rest of the country was shocked into paying attention on January 6. When thousands of people descended on the District in mid-November, encouraged by Trump’s insistence that they “stop the steal,” anti-fascist groups were quickly outnumbered. The police—decked out in riot gear—mostly kept the opposing sides separate, but it was clear they had much more tolerance (and at times outright camaraderie) for one side over the other.

Before they threatened Congress, white supremacists had been targeting local activists for months; Dawes was not interested in a repeat of the night of November 14, when he says he was stabbed by a member of the Proud Boys.

Dawes says his only goal that day was “to keep everybody safe.” But after overhearing a group of Proud Boys say they intended to “go out hunting and clean up the streets,” he knew he was in for a long and potentially dangerous night. When a cop pointed to Dawes’s tactical vest and all but challenged him to go head to head with the domestic terrorists—some of whom were not-so-covertly armed with clubs, bear mace, and other weapons—Dawes once again found himself in the middle of chaos. He narrowly avoided being seriously injured when a knife was thrust into his vest by one of the alt-right agitators—several others weren’t as lucky.

A ‘Stop the Steal’ rally outside of the Capitol in November 2020. | Photo: Kristine Jones

Dawes says he was not at the Capitol on January 6; he was helping to coordinate transportation for others concerned they wouldn’t be able to get home safely that night. But he wasn’t surprised by the lack of police presence around the mostly-white mob. “They were older white men who used their privilege to storm the Capitol,” he says. “God forbid if any of us went anywhere near the Capitol steps—we’d be shot with live ammunition. Meanwhile men with weapons and zip ties used their power to do what they wanted and [most will likely] get away with it.”

Dawes cites precedent: in 2013, Miriam Carey, a Black woman, was shot to death by the Secret Service and U. S. Capitol Police after she made a U-turn at a White House checkpoint. A car chase took Carey to the Capitol and a nearby Senate office building where officers discharged 26 bullets, killing the 34-year-old while her 13-month-old daughter was in the car. Eight years later, the list of Black lives lost too soon—or ruined long before they even got a chance to begin—is painfully long.

Photo: Kristine Jones

While he sifts through the fallout from months of what Lewis might not call “good,” but certainly “necessary trouble,” there’s one thing Dawes isn’t going to do: stop fighting for Black futures, including his own. “We want to show people the circumstances of how these people died and how horrific it was,” he says. “If it happened to them and it happened to someone who looks like me, or my sister, or my brother, it can happen to anyone.”