Kristine Jones Fights Protest Fatigue

Kristine Jones is more comfortable behind the camera than in front of it.

If you’ve been to a protest march or rally in Washington, D.C. in the last few years, chances are good that you’ve seen Kristine Jones. Even more likely is that Jones has seen you, probably through the viewfinder of her camera. It’s human nature to put people into tidy categories, and it’s not wrong to call Jones a photographer. But she’s also an activist, a mother, an artisan product development and marketing consultant, a wife, a real estate agent, and a generous friend. I’m exhausted just typing that list, so I’m not surprised when Jones tells me recently that she’s tired.

“I feel like I’ve been protesting something for a very long time,” Jones says. “The burnout is crazy. I’m feeling a little burnt out. I swear to god if it goes badly in November, it’ll be very bad. How can people sustain that anger and frustration?”

Jones has more than earned the right to be burnt out. She was just a senior in high school when she attended her first protest rally on June 12, 1982. Jones and her sister took a bus from West Hartford, Connecticut to New York City, joining one million people in Central Park in what would turn out to be the largest anti-nuclear protest and one of the largest political demonstrations in U.S. history.

“Listening to the speakers I thought, ‘These are my people,’” Jones says. “I felt as if I was a part of a club. I felt the rage and the injustice.”

All photos courtesy of Kristine Jones

From 1991 until 2002, Jones and her husband lived abroad while working for non-profits in Azerbaijan, Vietnam, Bosnia, and Jerusalem. They worked with internally displaced peoples (IDPs) and immigrants; on long drives through Azerbaijan in the mid-’90s, Jones and her husband noticed that once-plentiful trees seemed to be disappearing. They weren’t wrong: the IDPs were living in abandoned buildings and burning the trees for heat and to cook their food.

Growing up, Jones had spent a lot of time hiking through national parks, but she didn’t immediately see the connection between her anti-war work and the climate crisis. “I thought if we couldn't stop wars and conflict, there was no way we would be able to stop deforestation,” Jones says. “But it also seemed like [deforestation] was a superficial problem considering what else the refugees and IDPs were facing.”

Even when they returned to the states in 2002, Jones continued to focus her activism within the anti-war, women’s rights, and immigration movements. “Basically I thought the climate crisis didn’t need me,” Jones says.

The climate crisis doesn’t just affect coral reefs and obscure tropical frogs; this devastating loss of biodiversity is important, for sure, but focusing entirely on stereotypical crunchy-granola environmental issues may allow the naysayers—especially those that feel disconnected from, or somehow above, nature—to have a false sense of security. But for at least three decades, the Brookings Institution has known that “the greatest single impact of climate change may be on human migration,” and it has estimated that “by 2050, 150 million people could be displaced by desertification, water scarcity, floods, storms, and other climate change-related disasters.”

It wasn’t until recently that Jones began to connect the dots between the issues she had been championing for decades and the climate crisis. “The concept of melting glaciers was a concern, but these ideas forming in my head were not based in science or logic, I was just acknowledging that it was bad,” Jones says.

When she had a child of her own, Jones says her connection to—and the urgency she felt to help protect—Mother Earth increased. But it took another young person, the teenage Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg, to really light a metaphorical fire under Jones. “Having a young girl look at you—without trying to make you feel better—and say ‘What the hell are you people doing?’ is pretty shocking,” Jones says. “It was a wake up call. I thought, ‘What the fuck are we doing?’ She made me feel like we should all be doing more.”

No one can accuse Jones of not doing enough over the years, but instead of slowing down, she sees a direct correlation between her increasing age and fervent activism. And she’s not alone: she says it’s not uncommon for her to find herself surrounded by “mostly old ladies,” at protests. “I think it's mostly women because we care, but also because for the last 100 years we have been fighting for so much that it must be in our DNA,” Jones says. “At 55, you’re invisible anyway so it doesn’t matter so much what people think. We just can’t take this shit any more. We’re tired.”

All photos courtesy of Kristine Jones

Despite frequently insisting that she’s exhausted, Jones’ seemingly bottomless energy suggests otherwise. During our nearly four-hour phone conversation, Jones recounts how she broke her ankle on the fourth day of a six-day backpacking trip through Alaska’s Wrangell St Elias National Park and Preserve. Her foot was in a boot for months and she relied on crutches—but that didn’t stop her from going to the Capitol on the morning of October 11, 2019, to photograph a “die-in.” Jones’ friend was battling cancer and participating in the action to persuade Congress to allocate more money for late-stage cancer research. Afterwards, Jones walked (slowly) up the hill and joined the first of Jane Fonda’s Fire Drill Fridays rallies.

Jones, who says she owned several of Fonda’s workout outfits in the ‘80s (“I think I liked the outfits more than the actual workouts”), was moved by Fonda’s passion and her ability to articulate the complexities of the climate crisis. But in the end, Jones says it’s kindness that keeps people engaged, no matter the issue(s) at hand.

“I don’t judge anyone because I’m never really in it—I’m usually on the periphery,” Jones says. “Unfortunately, there are people in the movement who are a deterrent. When you’re not kind, and when you’re not encouraging, and when you look at people like you’ve never seen them before, it makes it hard for people to stay. All it takes is for someone to be kind like Jane Fonda.”

Jones subsequently attended about half of the fourteen D.C. Fire Drills, missing several only because she eventually had to have surgery on her ankle. In November and December, she was arrested for civil disobedience twice—partly because she had one prior arrest on her record (in conjunction with the Poor People’s Campaign), and partly because she says she was “torn between photographing the event versus being a participant. Which was more important?”

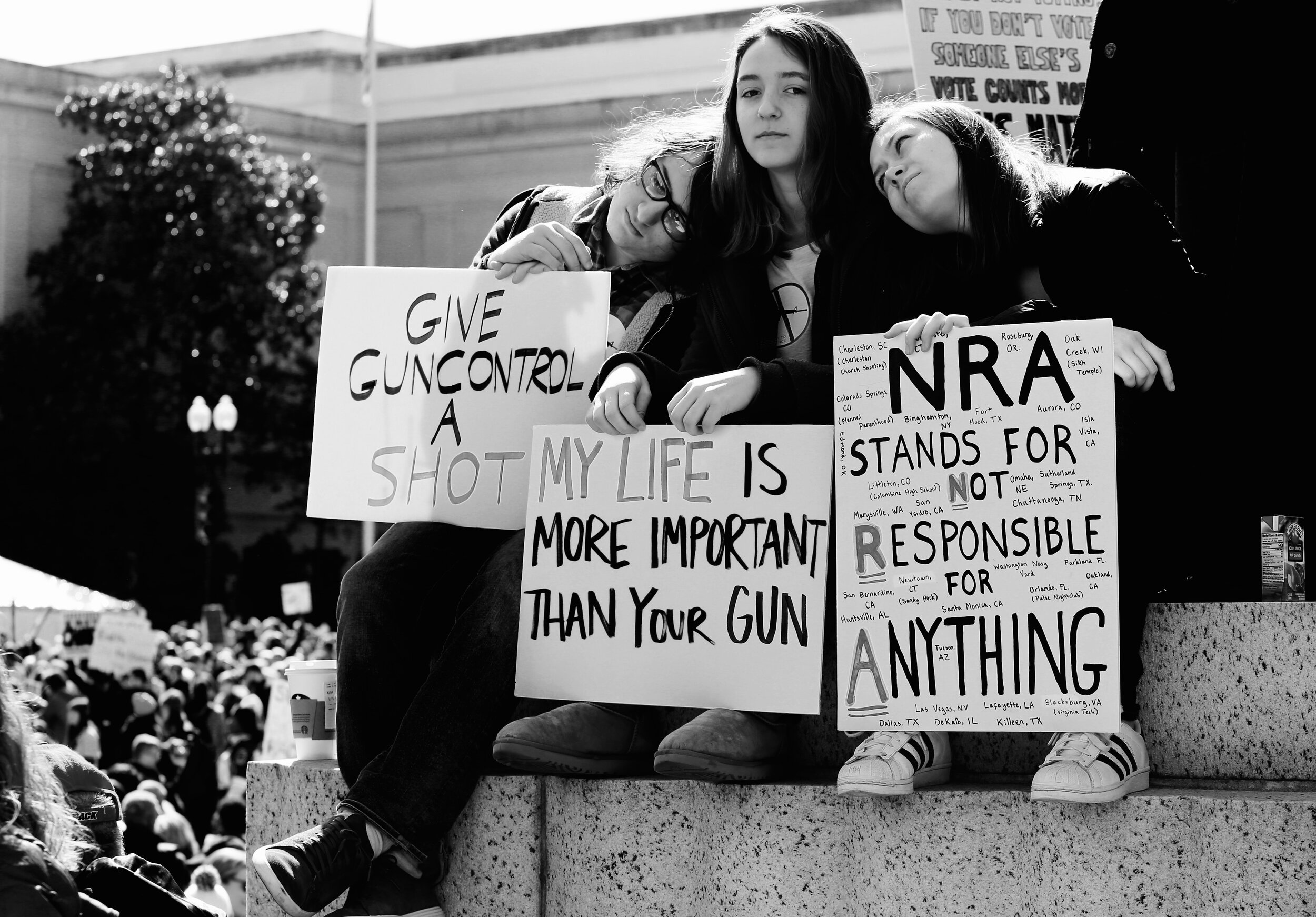

Sometimes, Jones says she thinks that taking photographs is more useful in the grand scheme of things. Despite a recent hard drive crash and Jones’ claims that she “does nothing” with her photographs, that’s not exactly true. She posts them to her personal Instagram account, sends them to the people who appear in the photographs, and allows organizations to use them for fundraising purposes. She’s the perfect friend with which to attend a march—documenting everything so you don’t have to; like an Instagram husband, but much more attentive and festively attired.

I understand the photographers’ dilemma—always hidden behind the camera and never in front of it—so I’m forever indebted to Jones. Just a few hours after we first met, she beautifully captured several Fire Drill Friday moments that were particularly meaningful for me. Yes, I’ll always have the memories, but it’s extra nice to have the photos as well. Despite all evidence to the contrary, Jones still calls herself an “amateur photographer.” Having witnessed her in action, I’d say she’s being much too modest; she manages to capture the complex emotions and fiery passions of her subjects—no small feat in the crushing crowds and chaotic atmosphere of a large march or protest rally.

It’s not surprising that Jones says she honed her quick-reaction skills in conflict zones abroad. “The injustices—that’s what I gravitate towards,” she says. “At first, I would just take pictures of things that interested me. The subject matter was always some sort of conflict.” When Jones and her husband returned to the states, she began photographing anti-war rallies. Balancing her dual roles as both participant and observer can be tricky, but sometimes—like during her second arrest with Fire Drill Fridays—she manages to do both.

“I’m always seeing [an event] as I would be as a photographer,” Jones says. “I want to be a part of it, but I also feel like the value of having the photograph is useful—it’s something you can share, it’s a record.”

Mostly, Jones is looking to capture—and then convey to others—the same passion that continually drives her to the frontlines. “I'm looking for the thing that says ‘I’m here because this is so fucking important to me,’” Jones says. “When people look at the picture they must think, ‘This person is so worried about this situation,’ and I’m trying to say ‘Are you not as upset as they are?’ I want to share other peoples’ sense of urgency and have people feel the same way.”

All photos courtesy of Kristine Jones

In between the marches, rallies, and protests, Jones also somehow finds time to devote to myriad political causes. Jones lives just a few blocks from the Capitol, but for her birthday in 2018 she took a trip to Texas to work on Beto O’Rourke’s senate campaign; in 2017, she traveled to Alabama to help Doug Jones defeat former Alabama Supreme Court judge (and alleged sexual assaulter) Roy Moore. She canvasses and helps with voter protection outreach for the DNC, advocates for immigrants, and runs another Instagram account called I Vote Democratic, after she discovered that “a lot of people really felt like they didn’t see themselves in our party anymore,” she says.

Even though Jones admits that she can see the appeal of the concept that “ignorance is bliss,” she still sees the value in trying to work within the current system to affect change. “You look at these things, and how much work it takes, and the setbacks, and the dealing with the government, and the B.S. and the deals. It’s depressing,” Jones says. “Sometimes my head wants to pop off. But then I can’t let it go. I see it and think ‘Ok that’s just not right, I need to do something about that.’”

Jones and her son worked hard on Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign, and they were understandably morose on the morning of November 9, 2016. Her son tried to console his mother by scribbling a message of hope on her bathroom mirror. “We just need to work a lot harder to make change,” he wrote. “Always forward.”

Four years later, Jones is still angry. But she’s trying to channel that rage into something productive. Not doing something has never felt like a viable option for her, but despite the inevitable burnout, Jones says now is not the time to be complacent. “People didn’t think this was such a big deal in 2016,” she says. “I felt like I was the boy who cried wolf, but I was right actually. I’m afraid that if I don’t get out there, it’ll be worse.”

Although she cherishes the time she spent traveling, Jones says that she “would never want to live anywhere else in the world.” One of the best things about living in the U.S. is that “no one is American—because everybody can be American,” Jones says. “You don’t look at someone and say ‘That person is American’ because we could be anybody. I have friends with German passports that say ‘I’m from Africa, I’ll never be German. But in America, people could think I’m American.’”

The years she lived abroad provided Jones with a fresh perspective; while she is the first to acknowledge that the U.S. has its flaws, her love for her home country runs deep. She says she cried when George W. Bush got reelected, but she has the opposite of a “love it or leave it,” mentality when it comes to how she views her role as a citizen. “We’ve got to fix [the U.S.] because this isn’t really who we are,” Jones says. “Plus, I feel like it’s everybody’s responsibility to do a little bit. We all live here. It’s like maintaining our home in a way.”

All photos courtesy of Kristine Jones

It may not always be easy, but Jones is trying to pass this sense of obligation on to her son, who graduated high school this year with significantly less fanfare than previous generations thanks to COVID-19. He has attended every Women’s March and is forging his own path as a somewhat-reluctant activist-in-training. Jones is cautiously optimistic about her influence. “I don’t ask,” Jones says. “We just have things that we do and that’s one of the things. But he would be good at it. Who knows, I might have created a Republican—but I hope not.”

The climate crisis is not a partisan issue or a singular, cataclysmic event—and Jones thinks that may be part of the problem. Americans, and humans in general, seem to be better at reacting to catastrophes than they are at preventing them. But even in these times of seemingly never-ending and overlapping crises, Jones sees an opportunity to motivate those who might, for various reasons, not think they can make a difference.

“It’s crazy how many people have found their creative outlet just because this moron is president,” Jones says. She says that her work trying to secure protections for immigrants (which are often motivated by looming legal deadlines) has shown what might work—or not work—as we try to address the climate crisis.

“With climate change, nobody sees the end, it’s not a big action, it’s not something that happened all at once,” Jones says. “It’s amazing what people can do when they’re forced to, at the last minute. But there almost needs to be a deadline associated at the end of it. I feel like, with the climate, there’s not that end date that’s scaring people.”

All photos courtesy of Kristine Jones

One of the main missions of Fire Drill Fridays is to try to counteract this very real problem of inertia—and light those metaphoric fires underneath people who may have never considered themselves activists in the traditional sense. It worked for me; I was arrested three times for civil disobedience and was lucky to have Jones as a fellow detainee for two of them.

It may be easy to dismiss a group of mostly white, middle class women (and especially celebrities) in zip-tie handcuffs as a meaningless publicity stunt, but Fonda says the arrests shine a light on her inherent privileges—and that’s part of the point. Jones has a similar view on the effectiveness—and often complicated optics—of civil disobedience. “It’s easy for us to get arrested,” Jones says. “I think it’s a big thing and I get nervous, but I know it’s not like other people’s experiences. I feel bad about our privilege but I understand the need of the theatrical aspect of what we do. It's important for us to stand up.”

Jones, a visual person by nature, also recognizes the lasting impact that a photograph can have on the historical record—for better or worse. “The visual of people getting arrested for the climate is a similar visual to that of Kent State [on May 4, 1970], or the visual that haunts Jane Fonda—of her sitting on that tank [in Hanoi]—these are all visuals that we keep in our head, so it’s useful.”

All photos courtesy of Kristine Jones

COVID-19 has changed life dramatically for almost everyone, and all of Jones’ pursuits have been affected in different ways. She says it’s weird being a real estate agent without in-person showings or an artisan product consultant with the future of trade shows uncertain. But the biggest change she has noticed is in her own neighborhood: after three solid years of not going a full week without some sort of protest, Capitol Hill is eerily quiet. There have been a few nurses advocating for better protections and car caravans along Pennsylvania Avenue, but for the most part, “everything has changed,” Jones says.

She’s still able to shoot portraits—wearing a face mask and using a zoom lens from a safe distance—and she acknowledges that it could always be worse. “I like to see how people make it through conflict—how they survive,” Jones says. “People lived in quarantine-like situations like this during the Bosnian war, and they still did art. They didn’t even have Netflix; we have Netflix. Most of us are not really suffering.”

In the current pandemic (and post-pandemic) world, the usual methods employed by activists may have to change, but not everything is obsolete. “The most important part [of activism] is—and what Jane Fonda did so amazing—is to make everybody think that they are important and crucial,” Jones says. “Jane was the best hostess ever, thanking everyone for coming and making sure everybody knew they were important.”

We may not be able to gather in the streets for the foreseeable future, but humans are remarkably resilient; the tools available today are just as varied as the activists themselves. Jones says she sometimes feels intimidated by new technologies, but she’s particularly excited about new opportunities to reach large groups of people without ever leaving home (Open Progress likens its texting tool to “knocking on digital front doors”).

“There really is something for everybody,” Jones says. “There is something that matches your skillset. Everybody has different levels of caring, different levels of putting themselves out there.” The level of participation may vary, but Jones thinks the very human need to feel as if we’re making a difference, no matter how small, is universal. “If people feel like they’re needed, it makes a big difference,” Jones says.

Whether she feels it or not, every movement needs people as dedicated and tireless as Jones. But even she admits that she sometimes needs a break. “Sometimes I just need to watch Real Housewives,” Jones says, laughing. “I want to watch stupid YouTube videos. I want to laugh. I want to not feel overwhelmed by all the crazy crap that’s going on. Who wants that dour shit all the time? Nobody does.”

We may not want it, but we all have our fair share of “dour shit” to deal with in life—ankles break, hard drives crash, graduations are cancelled, and candidates lose elections. But no matter how bad things get, Jones refuses to lose hope or even think seriously about slowing down. “When things seem bad, if I can go out and do something, that makes me feel better,” Jones says. “If you’re feeling helpless, help someone else.”

A RECIPE FOR CREATING AN ACTIVIST FOR TRUTH AND JUSTICE, BY KRISTINE JONES

Start with the following fiction books:

To Kill a Mockingbird, by Harper Lee

The Color Purple, by Alice Walker

Then add these three blockbuster movies:

Norma Rea (1979)

Silkwood (1983)

Dark Waters (2019)

Add non-fiction books that feel like fiction:

Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption, by Bryan Stevenson

Bury Me Standing: The Gypsies and Their Journey, by Isabel Fonseca

The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration, by Isabel Wilkerson

The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down: A Hmong Child, Her American Doctors, and the Collision of Two Cultures, by Anne Fadiman

Then throw some documentaries into the mix:

Roger & Me (1989)

Dolores (2017)

An Inconvenient Truth (2006)

Crip Camp (2020)

Bonus! For activists with kids or kids who want to be activists:

March: Book One, by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell