A Trailblazer is Riding Free

Photo: Kristine Jones

I don’t remember when I first met Kathalene Kilpatrick, or how I got to wherever in Washington, D.C., our introduction took place. The most likely location is outside of a tall, “unscalable” fence that encircled Lafayette Park and the White House in the last six months of 2020 and beginning of 2021. A few weeks after George Floyd’s late-May murder, Mayor Muriel Bowser directed city officials to paint “BLACK LIVES MATTER” in large, yellow block letters stretching from I to H streets just outside of the park. The temporarily-car-free plaza, bisected by 16th Street NW, became a gathering space for activists, trauma tourists, and anyone else who felt they had something to say or see.

The Black Lives Matter Memorial fence was an unofficial, living makeshift monument to (mostly) American lives and dreams lost too soon; it both seemed as if it would last forever and was constantly in danger of disappearing overnight. Personal experience can be painful, but it’s a surreal privilege to witness history being made in real time as old, ordinary pieces from the past are cobbled together and reimagined into something new and extraordinary. Anyone moved in any way by the messages beamed out—at a time when most people suddenly had little to do but pay attention—may not realize there is a relatively small band of very real guardian angels to thank, at least in part, for their transformation.

Members of the scrappy, unofficial chosen fence family, which almost always included Kilpatrick and other equally-impressive women, remained at the plaza through rain, snow, wind, oppressive humidity, petty political photo ops, and Stop the Steal rallies. The collective was one of the only constants in a chaotic period which included clouds of tear gas in the summer, tears of tenuous joy and champagne spritz on election day, and covid droplets spewing from MAGA mouths planning a January insurrection.

More than a year after the fence finally came down and the park reopened, it seems now that the show of force was mostly a farce; a death rattle by the flailing Trump administration meant to intimidate. Instead, the main thing it proved was that chain link could became a canvas for protest posters, artwork, and other mementos of the movement—as long as it was lovingly maintained and protected by a small, but resourceful group of passionate people with a singular purpose: to fiercely defend the promise of a country that had almost always let them down more times than it had lifted them up.

Photo: Kristine Jones

A BAD START

On August 29, 1942, Kathalene Hughes Kilpatrick was born premature and severely underweight at a 666 street address in Tallahassee, Florida. That the roots of her family tree are tangled, gnarled, and hardy shouldn’t be a surprise; in a nation stocked by waves of immigrants and built on the labor of those they enslaved (officially or otherwise), things get hard real fast. She admits that some details of her long life have blended together over the decades in a game of generational telephone. “At the age of 80, it takes a little thinking to go back that many years,” Kilpatrick says recently, and apologetically.

But other things only become more clear in the rearview: She knows for sure that at least some of her ancestors had no choice whether or not they wanted to come to America in the first place—and few good options once they arrived. Her relatives are mostly Black, but also Cherokee and Seminole, a lot of whom appear to, at least anecdotally, have possessed especially robust genes. Several lived full, healthy lives well into their 100s, and if they were anything like their still-living legacy, they no doubt made the most of their limited opportunities and chose gratitude when they had a choice. Kilpatrick mentions several times that, even into her eighth decade, she still has “a sound mind and good vision.” But even if she didn’t—and if it was possible to get one—I don’t think Kilpatrick would accept a cosmic do-over.

Some people might be hardened after a life like hers, one in a which a lot of time appears to have been spent doing the right things for the wrong people; but there is no trace of bitterness in her voice when she says, “Because I love all people, people seem to love me,” or “I am very happy because as the Bible states, my latter days are better than the beginning days.” I know the first statement is accurate because I’ve seen its truth with my own eyes—but I can only hope the second is as well. Kilpatrick never asks for anything more than her fair share of equality—and even that appreciation of self seems to have arrived only after a lifetime of karmic debt operating in the red from the very beginning.

“My life just started out in a bad way,” she says.

Photo: Kristine Jones

Kilpatrick’s first days—and many that followed—were by any metrics, indeed quite bad. But she is careful not to be too critical of others, including her parents, siblings, ex husbands, friends, coworkers, extended family, and even passersby. Like a lot of women, she lavishly compliments others and directs her harshest thoughts back at herself: when presented with photos of herself, she scrutinizes her appearance despite the indisputable fact that she always looks impeccable. She constantly apologizes for things that I would have never thought to consider as intrusions in the first place.

While she was growing up in the post-war Florida panhandle, Kilpatrick’s parents must have ached under the weight of juggling several kids with multiple jobs including nursing, phonograph repair, at a furniture store, and in a beauty salon. She says it was a stable, if also stressful and largely loveless, environment. But after she became a young single parent herself, Kilpatrick mostly thinks her less-than-ideal childhood was a fair price to pay for her family to achieve the American Dream: “They worked hard,” she says. “But they always had homes.”

When Kilpatrick was 16 in the late ‘50s, she was raped by a religious leader and family friend, and forced to give birth to a child she didn’t choose but loves unconditionally, nonetheless. “I had no choice because it was 1959,” she says in late September 2022, just a few months after the Supreme Court strikes down Roe v Wade. “I don’t think a man should have a say—period. It’s not about a man. It’s not about the faith. It’s a power thing. It’s about doing the right thing.”

Photo: Kristine Jones

For most of her life, Kilpatrick has followed in her family’s multitasking, hardworking footsteps, usually with at least one of her feet on the gas pedal or brake of a public transit vehicle or tour bus. Briefly, she drove a taxi cab while she was enrolled in night school and raising two children on her own. She’s been married twice, divorced and widowed; one husband was haunted by demons from his military service in Vietnam, and another inspired Kilpatrick to move from Florida to D.C. in the late ‘60s “to put as much space between us as we could,” she says.

In the early ‘90s, her son-in-law violated a restraining order, marched into a Fort Lauderdale grocery store, and shot himself and Kilpatrick’s only daughter in the head while she worked. He died at the scene, but her daughter lived in a hospital for more than 30 days, eventually dying in Kilpatrick’s arms and leaving behind a teenage son. Kilpatrick cared for her grandson too, until he enlisted in the Navy (and died young in a motorcycle accident). She credits God for guiding her through the darkest days, and says, despite it all, she tries to focus on the light and considers herself lucky.

“God has just been really good to me,” she insists.

STATE OF INJUSTICE

If I had boarded a D.C. Metro bus back the ‘70s, the driver most likely been male, and probably also white. Or the bus driver might have been Kilpatrick, who was the first female to operate buses in Tallahassee before also driving for Metro and other public and private transit fleets.

During the summer of 2020, I mostly walked everywhere. But even if I had taken one of the buses that stops frequently outside my apartment—and Kilpatrick was on it—she wouldn’t have been behind the wheel. Although I didn’t know it when we met, at an age when others with lesser credentials are reaping the earned rewards of retirement, Kilpatrick spent nearly her entire seventh decade living down on the same streets that she had once so nimbly navigated from above.

It’s hard to go far in the world without being confronted with marble monuments erected to, and by men who decided it was they alone who made America great. Outside of Union Station, the District’s main transit hub, stands a gleaming white statue of Christopher Columbus, erected in 1912 and looming nearly 50 feet tall over a grass-and-concrete ellipse. Today, the fountain’s basin is empty, covered in white-washed wooden boards; it’s unclear whether work on the monument has just begun, paused, or if it was a temporary fix that turned permanent by neglect.

Early in the pandemic, as planes, trains, and buses coming in and out of the city slowed to a trickle (and still haven’t reached pre-2020 levels), more tents and temporary structures sprung up in—and were inhumanely cleared from— triangle parks, underpasses, and a lot of the land surveyed by Columbus: The man who “discovered” America, sentenced in stone for all of eternity to watch what it had become. The plywood continues to be splintered by the feet of too many tourists, protestors, birdwatchers, pigeons, and people who, for one reason or many, by choice or circumstance, are dangerously close to falling through the cracks themselves. People whose backstories overlap more often than not with Kilpatrick’s: they’re Black, or Native, or a murky mix of marginalized identities, homeless on land that has been stolen from someone at least once.

Through it all, they emerge with improbable empathy and energy, but low on favorable options. Every day, in a country famous for its bottomless buffets and glut of Airbnbs, too many good people are still looking for a sturdy and safe place to spend the night. While Kilpatrick lived for a time outside of Union Station, most nights in early 2020 she spent curled up less than a mile north of the White House, on the storied steps of St. John’s Episcopal Church. Referred to as “the President’s church,” even in the times before Trump’s now-infamous upside-down Bible photo op, the yellow Greek revival house of worship was consecrated in 1816.

Photo: Kristine Jones

A more compassionate and uncontrived portrait was taken not too long before Trump’s: Made by Kristine Jones, the black-and-white shot shows Kilpatrick sitting alone on a city bench in downtown D.C. She’s looking outside of the frame, considering what, or who, we can’t know. Or maybe she’s thinking about nothing much at all, figuring she’s earned the moment of rest in a life spent on the move. Maybe she’s filled with a mix of awe and annoyance that life is somehow too full and yet falls short on both pure tragedies and comedies; maybe she’s thinking about how nothing—and no one—is ever objectively all good or all bad. Or maybe that’s just how looking directly at Kilpatrick’s indirect gaze in the photo makes me feel. Ambiguity makes it all interesting, but uncertainty is nerve-racking to navigate alone. It’s easy to lose your way or get turned around when you’re too tired to know exactly what it is, or who you are supposed to be looking for—or at.

Kilpatrick, of course, looks good as always, despite her weariness and the weather, wrapped in a nest of pristine jackets and fuzzy scarves, with a shiny, chic purse dangling from her shoulder. She holds a stark sign that succinctly sums up the state of her outside circumstances only; her inner thoughts may always largely remain a mystery. We might not be able to determine the state of her mind with vision alone, but luckily for the rest of us, when she sees something wrong, she usually says something.

A SMOOTH TRANSITION

Kilpatrick’s been dipping her toes into activist waters, at least unofficially, since the early ‘60s when a group decided it was time to integrate a Tallahassee movie theater. She says she remembers segregation, cross burnings, and student protests, but decades later, she describes her collective memory of tumultuous time periods with umbrella terms that both seem innocent (“very calm”) and slightly more insidious (“Southern hospitality”).

She was driving a public school bus, one of, if not the very first Black women in the area to do so, when Florida began to integrate. If the students had a problem with it, they never said as much to Kilpatrick—she was in the driver's seat every day and they weren’t there yet. “They found a vacant seat and that’s where they sat,” she says. “It was a smooth transition.”

I’m positive that she’s incapable of abusing whatever power she earned over the years, but I also get the sense she never felt quite right apologizing much for it either. And still, even after all that she’s experienced before and since the official end of segregation, she still thinks the solution to division in America is simple. “We should have equality,” she says. “It shouldn’t be a problem to live together and get along.”

Photo: Kristine Jones

Today, the idyllic Florida of Kilpatrick’s early years may feel as foreign as a time when women were rarely allowed—let alone trusted—to drive their own destinies (or vehicles) and make their own choices (or maybe not). But it was a place that allowed Kilpatrick to hit a lot of the milestones newly available to women of her generation: She was a Brownie, a Girl Scout, and Miss Freshman at Lincoln High School. As a teen she played softball, volleyball, and basketball. “I was a guard and we were a little hard to beat,” she says, flashing a mischievous smile in the way she handles disclosing most of her accomplishments, no matter how impressive they may be: humbly and humorously with more than her fair share of humility.

Kilpatrick has been the subject of several features over the course of her illustrious life—for both her ups, as well as her downs—but it’s not long into a conversation for this profile that she apologizes for focusing so much on herself. “If it’s too much, get the best part and leave the rest,” she says. “You surely don’t have to include everything,” she offers, as if that’s even possible with someone as prolific, selfless, beloved, and thoughtful as she is.

Maybe her wisdom comes from having been a Christian since the ‘50s, one who despite a lifetime of navigating a world built purposely to oppress her, still maintains an unshakeable faith in the goodness of humanity. Or maybe it was just learned the hard way, by a breadth of extraordinary experience that includes photos with presidents and chauffeuring a bus full of nuns who were also nurses.

DO YOUR OWN THING

Kilpatrick has been working and volunteering (officially or not) in some capacity and almost constantly since she was a teenager. Her resume lists so many inspiring entries for anyone, let alone a Black woman from the South, that it begins to feel like a frustrating question without a good answer, or a crude, unfunny joke with no payoff: What do you get when you deliver a bus full of nuns, politicians, and “the most famous band in Panama” safely to their respective destinations? Depends on who you ask and their metrics for success, but the best drivers usually aren’t afraid of the unexpected detours. And if they’re really special, like Kilpatrick, they’re able to turn their personal pain into inscrutable but inspiring photo ops, spinning their own garbage into gold for others to reap benefits historically denied to them. They bring souvenirs back for the rest of us who may not be able to get there just yet—or ever, on our own—but are willing, at the very least, to pay attention and expect nothing but gratitude in return.

Kilpatrick has volunteered in hospitals, libraries, and at the DNC headquarters; she’s been a public school tutor, an election worker, and a foster grandparent, receiving recognition from at least two sitting presidents (Clinton and Obama) for her myriad efforts. Photos fade and certificates can be damaged in a leaky storage unit—but there’s a better reason Kilpatrick doesn’t put much stock in material possessions. Despite the well-deserved accolades, she’s always known what really matters in the end: “The only real true thing is love,” she says. “You can’t live on Mother Theresa’s legacy. You’ve got to do your own thing.”

Photo: Kristine Jones

Today, Kilpatrick tries to sprinkle pleasures in between the protests, but mostly she can be found doing a combination of both. She lists her hobbies as “reading, writing, drawing, and helping (assistance).” She says she very much enjoyed driving tour groups across the country to California, and loved the Hoover Dam, the Grand Canyon, and “seeing all those lights in Las Vegas.” But no matter how much she sees or how far she goes, Kilpatrick always comes back to the state where she feels most at home: her unconditional love for others. “Driving buses was very interesting,” she says. “But ultimately it just helped me take care of my kids.”

Kilpatrick has always been busy, working hard to keep herself (and others) afloat. Even as she fights the strong currents always seemingly working against her, she still tries to make the most of her limited time down on earth. She advocates for the homeless (work she did while unhoused herself), mentors foster kids, and offers a seemingly infinite amount of smiles or encouragement to a number of people who still call her “Miss K,” or simply, “mom.” When Kilpatrick thinks she has texted me too early, she offers an explanation wrapped in another unnecessary apology: “I am so sorry,” she says. “I text a lot of homeless people early in the morning to wake them up and sent yours by mistake.”

Photo: Kristine Jones

Whether she has a history with them or not, she has a kind word to offer most people we pass inside of Union Station. Outside, in a new shadow cast by old Chris, she tells a tourist not to sit down on a step because it’s covered in bird droppings. She greets strangers as if they’re friends, and some quickly turn from the former into the latter after receiving a well-timed compliment conjured out of thin air or common interest. She talks about a North Carolina basketball team with a person sitting next to her because of their t-shirt and instantly recognizes and hugs an old friend who is making their rounds cleaning the station’s bathrooms.

Although Kilpatrick admits that, the older she gets, she may need to sit for longer than she used to—or accept help when it’s genuinely offered—eventually she always stands up tall for herself and at every turn, tries to protect others from the bad luck dump truck that has followed her too closely for much of her life. She is self-conscious about sometimes needing to rely on anything solid for support, but mostly just uses her walking stick to push cigarette butts and a pencil out of the way so no one accidentally slips on the slick stone floors.

She frequently says, “Let me tell you something,” often followed by a Bible verse: “Inasmuch as you have done it to one of the least of these my brothers, you have done it to me.” It’s clear that not only does she practice what she preaches, Kilpatrick has perfected it. She is such a local celebrity around certain D.C. landmarks that I find myself wondering if there’s any historic moment or famous person she hasn't encountered in some capacity while doing her own thing over the years.

My suspicion is confirmed when our unofficial interview officially ends. We’re eating burgers at Shake Shack when Kilpatrick queues up a video on YouTube and slides her phone across the table. It takes me a few moments after she hits play—on a music video for the early-2000 hit earworm, “Thong Song,” by R&B singer and Baltimore native, Sisqó—to get my bearings and understand not only what I’m looking at, but why.

She’s transported me back to my teenage years, but not in an attempt to make a Christian comment on the morality of a song composed of poetic phrases such as “She had dumps like a truck, truck, truck,” and “Thighs like what, what, what.” One of the ever-present bangles jangling on her wrist might feature a charm that says “Earth Angel,” but Kilpatrick is no pearl-clutching saint. She’s also not exactly a star either, at least not in a video as memorable for what it doesn’t contain (many clothes) as for its catchy chorus. She doesn’t have a recognizable cameo, per se, but as one of only a handful of people—man, woman or otherwise—with skills to drive the standard shift Baltimore bus in the shoot’s Miami beach location, Kilpatrick was integral to the final product.

Kilpatrick says she was fired from The Pharmacy Corporation of America (where she was the only Black woman among more than 50 employees) for speaking out about the need for equal pay. She stopped driving for Metro because she felt that the bus wasn't safe to drive and the agency pushed her (and other drivers) to continue past her comfort zone. She says she was following the safety guidelines outlined in official manuals and always tried to do the right thing: “I always got my proper rest and had safe equipment,” she insists.

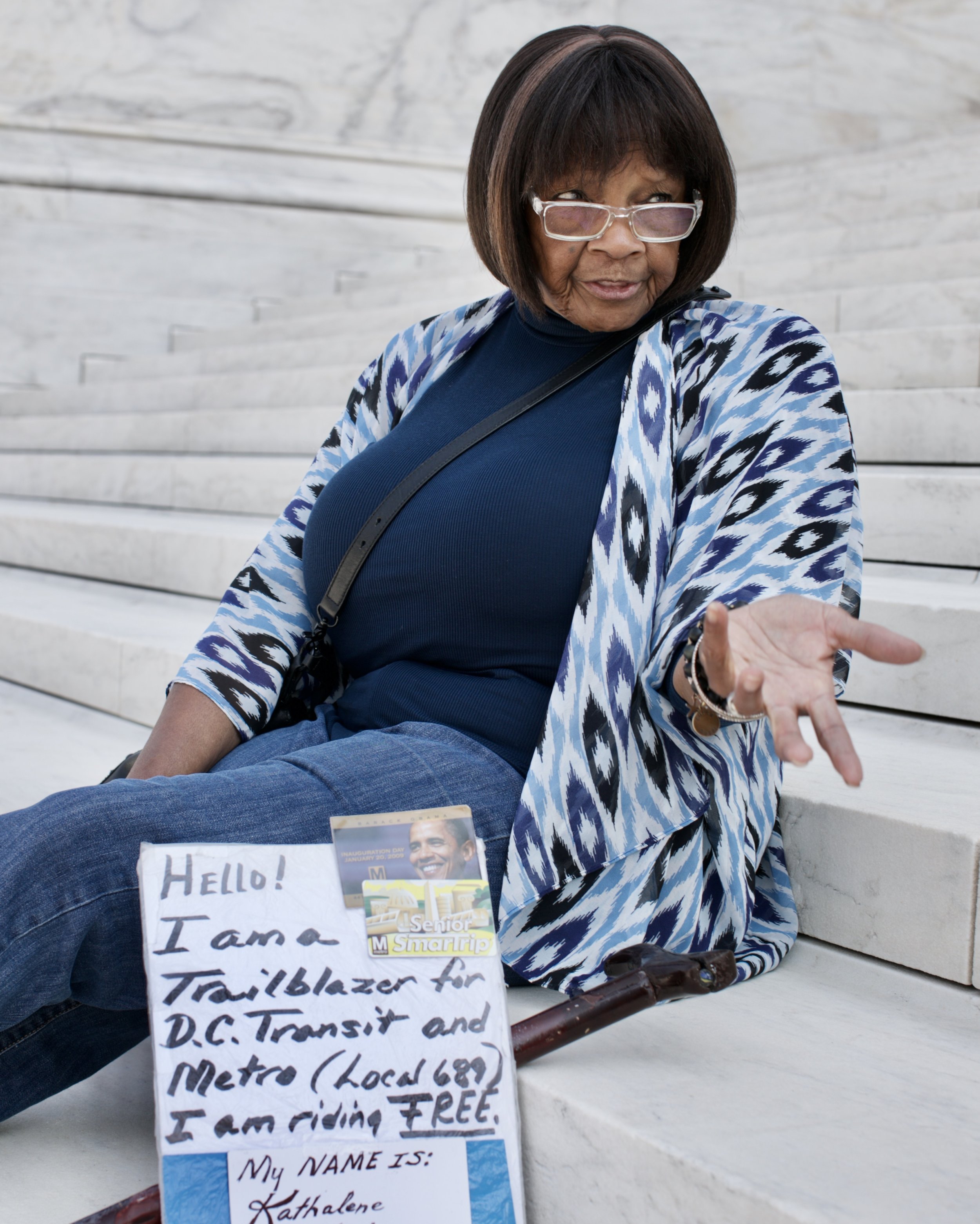

Since she left, she’s received nothing but the runaround from governmental agencies regarding records and benefits. As a result, she’s also been engaged in an ongoing, unofficial protest of her own (Kilpatrick v Metro) that she explains to me while we’re sitting on the steps of the Supreme Court under the inscription “EQUAL JUSTICE UNDER LAW.” She carries a neatly-hand-lettered sign in her bag that formally introduces herself to city bus operators—some of whom she still knows—and explains why an otherwise respectful woman fully intends to stiff them, intentionally breaking the law every time she boards without paying the fare.

“Hello! I’m a Trailblazer for D.C. transit and Metro (Local 689),” the sign speaks on her behalf, naming union credentials and highlighting yet another type of passenger bus she’s qualified to operate. A copy of her CDL is attached to the paper, along with a picture of Obama in case anyone looking at Kilpatrick needs yet another example of a real, live trailblazer. She’s attached a valid senior Metrocard too, just to prove that yes, she understands the rules—she has always been, and still is, a woman of sound mind and vision, afterall—but sometimes, she disagrees.

Photo: Kristine Jones

She also sees that guidelines are rarely one-size-fits-all, morality isn’t always able to be rendered sharply in black and white, and systems don’t always benefit those they are purportedly designed to help. Look no further than all of the very real guardian angels, caught in cracks everywhere on earth, for proof that it’s often easier to advocate for others than it is to stand up for ourselves. Kilpatrick’s sign ends with a reasonable, but revolutionary statement made by someone who has more than earned the right to ask for whatever she wants—even if it is to do nothing. But in doing nothing, she’s saying everything, including refusing to pay yet again for the same privileges that others receive automatically, without even a fraction of the work she’s already put in.

“I am riding FREE,” her sign simply states. And like its creator, her message may not always officially work, but it always makes a difference.

SALVATION ARMY

Kilpatrick became homeless in the summer of 2012, like most people do: due to a series of unfortunate events mostly beyond her control. She was evicted from a senior housing complex in D.C. after bogus claims that she couldn’t pay her $49-a-month rent. She says that she was bitten with bed bugs almost immediately after she moved in; when she spoke up, filing complaints and keeping her unpaid rent in an escrow account as she was advised to do, she was still evicted in what she thinks was just another cruel attempt to silence her.

She says she chose to sleep outside on the streets instead of inside of shelters because she doesn’t like to feel controlled, unsafe, or confined. Despite incidents of theft, sexual assault, and other indignities disproportionately doled out to people who share her demographic details, she insists she never really that nervous or too scared sleeping outside. She repeatedly expresses gratitude for those who have helped her out, anonymously or otherwise, including a white man who used to seek her out specifically just to give her money several times a week. She never knew his name and they lost track of each other, but she’s certain he was an angel with whom she shared a philosophy and a few moments of kindness every week, if not much else.

Kilpatrick never complains about, or romanticizes, the struggles of herself and others. “It seems as if this life is not for me—it is for me to do for others,” she says. “This is fine, but I need a little break once in a while. I pray that I will get the service that I need if it comes to that point of time in my life.” Her faith may be invisible and unstoppable, but it’s not improbable. She believes miracles happen to her all the time, and with the right perspective, it appears that they do.

Photo: Kristine Jones

While she was taking one of her rare breaks in 2020 and sitting on a bench outside of a congressional office building on Capitol Hill, Kilpatrick recognized a sister-and-law she hadn’t seen in 13 years. Thanks to the coincidence—and ongoing financial support from particularly generous members of her chosen family—Kilpatrick now lives with her sister-in-law in Maryland. “I am very grateful to all of my friends who didn't want to see me on the streets nor leave me on the streets of D.C.,” Kilpatrick says, speaking both specifically to her own experience and universally. “For a senior citizen of the U.S. to live on the streets for nearly 10 years is a disgrace.”

Though she is off the streets, Kilpatrick still admits to feeling confined, forced by circumstance to share a home with someone she had lost touch with long ago. “I am inside now, although I am still in a homeless state,” she says. Space is tight, Social Security payments are small, and she’s currently working at the Salvation Army six days a week. She has Sundays off—and clearly has earned more than just one day of rest—but she’s learned how to lean on her patience, her people, and above all else, her faith.

“I trust God with all my heart and he has brought me through many trials and tribulations,” Kilpatrick says. “Footprints are real in my life because God carried me through all the obstacles, valleys, danger, toils, and snares. He is my healer, my provider, and my evening. That is the end of my story.”

A CLASSY LADY

Like all good stories about guardian angels, Kilpatrick’s time down on earth will eventually come to an end—but that inevitability seems too far in the future to worry much about right now. I’m counting on the power of a combination of prayer, positivity, and those God-given good genes. Yes, many things start off badly, but if you put in the work and change your point of view, there can be no limit to the fulfilling middles or happy endings.

Photo: Kristine Jones

By the time we meet again outside of Union Station, a few weeks after her 80th birthday, Kathalene and I have seen each other countless times. We’ve sat together, marched, danced, and protested alongside each other for more than two years. There are a lot of chances to exercise the right to protest in our nation’s capital and a lot of really unjust reasons to take every chance and choice we’re given.

I offer to carry her purse out of generational duty, genuine kindness, and because she deserves a break, not realizing it contains another heavy bag full of Queen Elizabeth commemorative coins. Her Majesty has only been dead a day or two, but after we finish our burgers, Kilpatrick plans to catch a bus to a coin shop to see how much they’re worth. She knows their value, so she won’t let them go for less, but she’s also never been one to squander a good opportunity when she sees it. I ask her if she was a fan of the Queen, and Kilpatrick says: “Oh, yes. I liked her purses and her outfits. She was a classy lady and always looked so put together.”

“Let me tell you something,” she says. “I just love people. You never know who you can touch. They might be going through something and fellowship will give them a different feeling. When you’re nice to people and change your attitude, other people change too.”

What unfortunately can’t be seen in any photo or read in any profile, is how changed I, and others, feel after just a few minutes spent in Kilpatrick’s presence. She exudes a sense of inner peace and genuine kindness that I suspect no outside force—no matter how corrosive—can penetrate. She clearly knows where she is, a woman of sound mind and vision in every sense of both words. Yes, she got dealt a bad start, but she’s always had a good sense of direction. She knows it was sometimes very bad where we came from, but recognizes that there is always some good mixed in there too. She always acted as if she knew where we were going, even if it took more than a few, twisting detours to get there. She knows that it’s worth the extra effort to learn how to drive a standard shift; even if she could have never predicted that she would end up on a pristine beach with Sisqó, surrounded by the finer things in life.

Photo: Kristine Jones

But no matter what kind of history or personal tragedy unfolds around her, Kilpatrick seems to have always possessed a superhuman ability to focus on the task at hand and fulfill her mission (chosen or otherwise) to the highest standards possible. Whether she was driving radio legend Cathy Hughes, “Washington’s premier Go-Go band” Rare Essence, authors, students on a field trip from Florida’s Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, groups from the CIA (allegedly), honor guards on their way to Arlington Cemetery’s Tomb of the Unknown, sports teams, members of the military to secure locations, or those nuns who were also nurses, Kilpatrick has remained steadfast in her love of all people—not despite their circumstances, but because she knows how much there is that we can never know about another person. She just starts with the good, and sees how far it can take her.

She comes from a hardy stock, so in some ways unavailable to others, she can afford to fight fiercely and patiently await positive results. No matter where she’s going or how far, she knows that we all deserve better, that progress is possible, and the finer things are always more fun if you share them. She has always deserved the right to ride free—not because of all the years she gave to a system that only takes, or the selfless acts of service she still willingly doles out, but because she’s a real human woman who deserves to be safe and feel clean.

Luckily for us, she’s determined to take as many people with her, and along for the ride, as she can. But if she needs to take a Metro bus to get there, one thing is certain: Kilpatrick won’t be paying the fare, and I think that’s more than fair. She’s paid enough already. The only shame is that she is no longer the one driving the bus—because there’s no one, not even Jesus himself, that I trust more to take the wheel than Kathalene Hughes Kilpatrick, D.C. trailblazer.

Kathalene was born into a country that has done nothing to make her feel good about herself and everything to ensure she feels as bad as possible—which she has stubbornly refused to do, anytime she had any real choice in the matter. But after all she’s done in her long life, Kathalene expresses so much gratitude for her good fortunes that she is still too modest to take credit for much of anything, or ask for help directly.

So that's why we started a fundraiser on her behalf.

So if you feel moved by her story—and whether you’ve met her in person, just through this profile or Kristine’s photos, or feel connected in spirit, mission, philosophy, style, or otherwise—I hope you’ll consider donating what you can to help lighten her load and balance the scales of injustice, if only for a moment: 100% of the funds collected will go directly to Kathalene to use where needed, specifically in this instance, but dedicated to all of those committed to doing the same, or so much more, to drive all of us forward.

❤︎ Thank you ❤︎