Antonio Mingo is moved by spirit

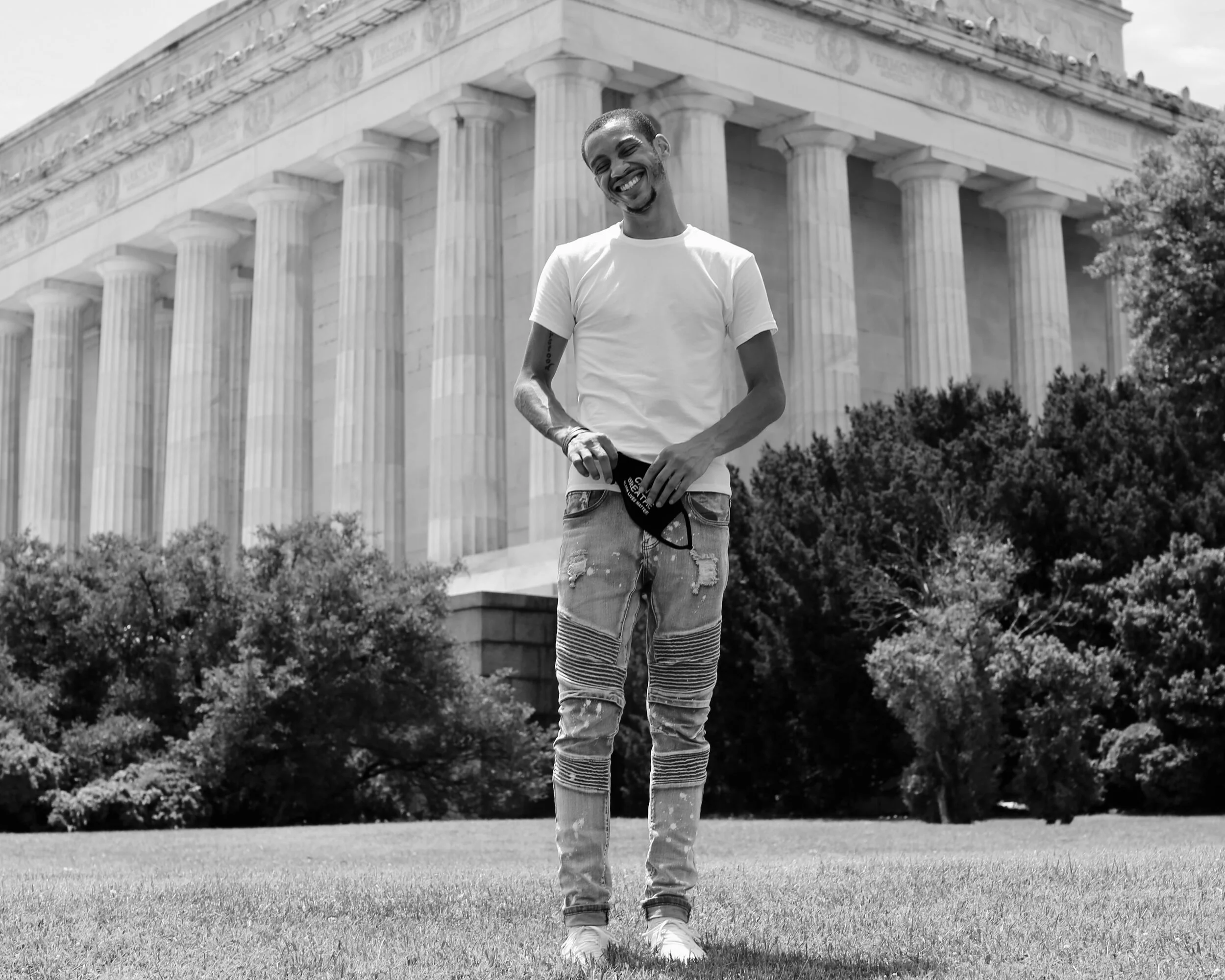

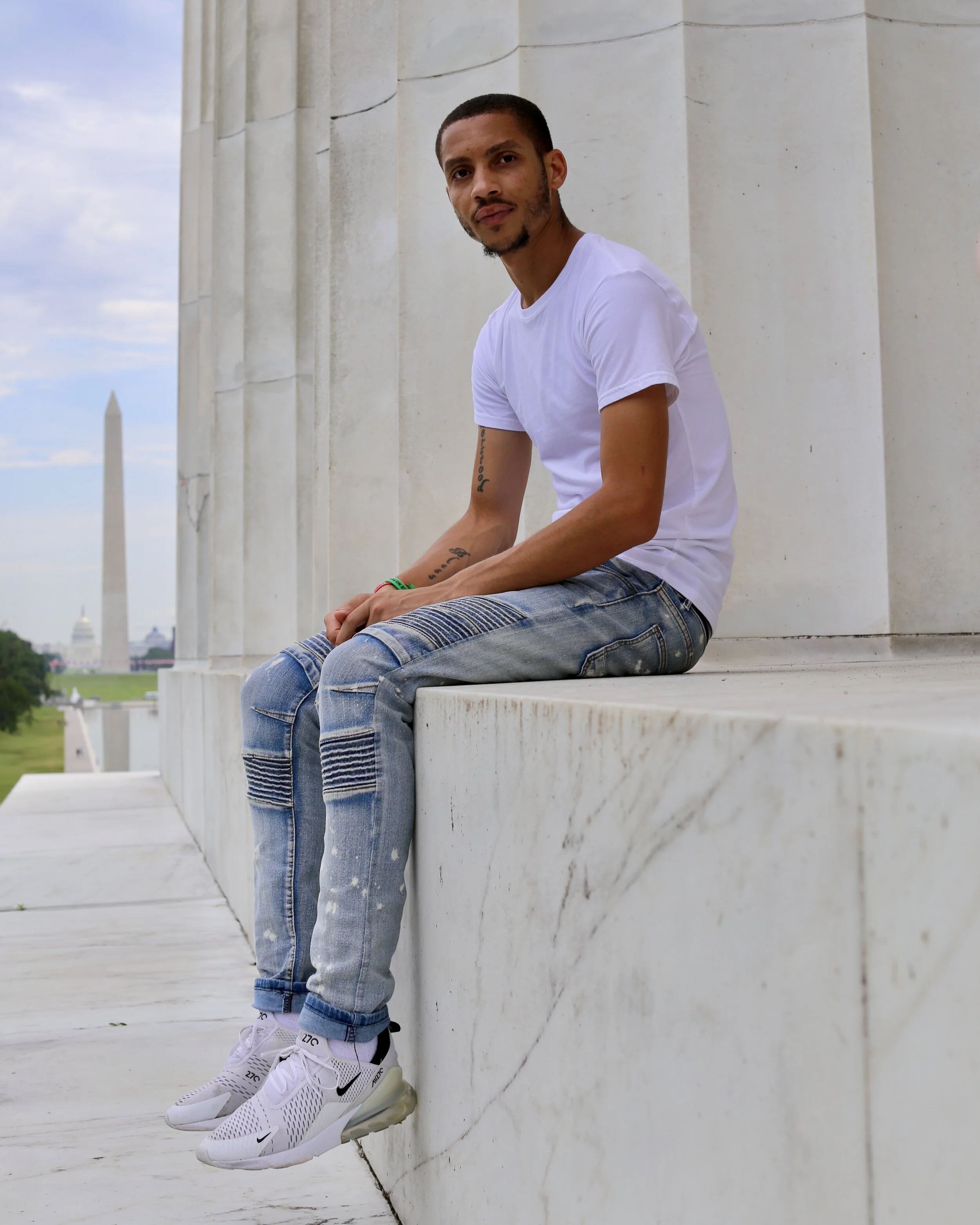

Antonio Mingo outside of the Lincoln Memorial. | Photo: Kristine Jones

In 2018, Makiyah Wilson went to buy ice cream when multiple shots were fired in the Washington, D.C. neighborhood where she lived. Wilson was struck and killed; she was just ten years old. Shortly after her tragic death, Wilson’s uncle marched more than 100 miles on foot from D.C. to Philadelphia, and in 2019 he did it again. The second time, he was joined by others who felt moved to make the pilgrimage in honor of Wilson’s too-short life, including D.C. native and co-founder of His Mission Organization, Antonio Mingo.

Mingo has two children of his own—including a daughter the same age as Wilson—but he has always felt a deep need to call out injustice no matter who it touches. When he tells me that he’s a passionate person, I believe him—not only because he repeatedly insists “I cannot tell a lie,” but because over the past two months, I have witnessed his passion, and its lasting impact, firsthand.

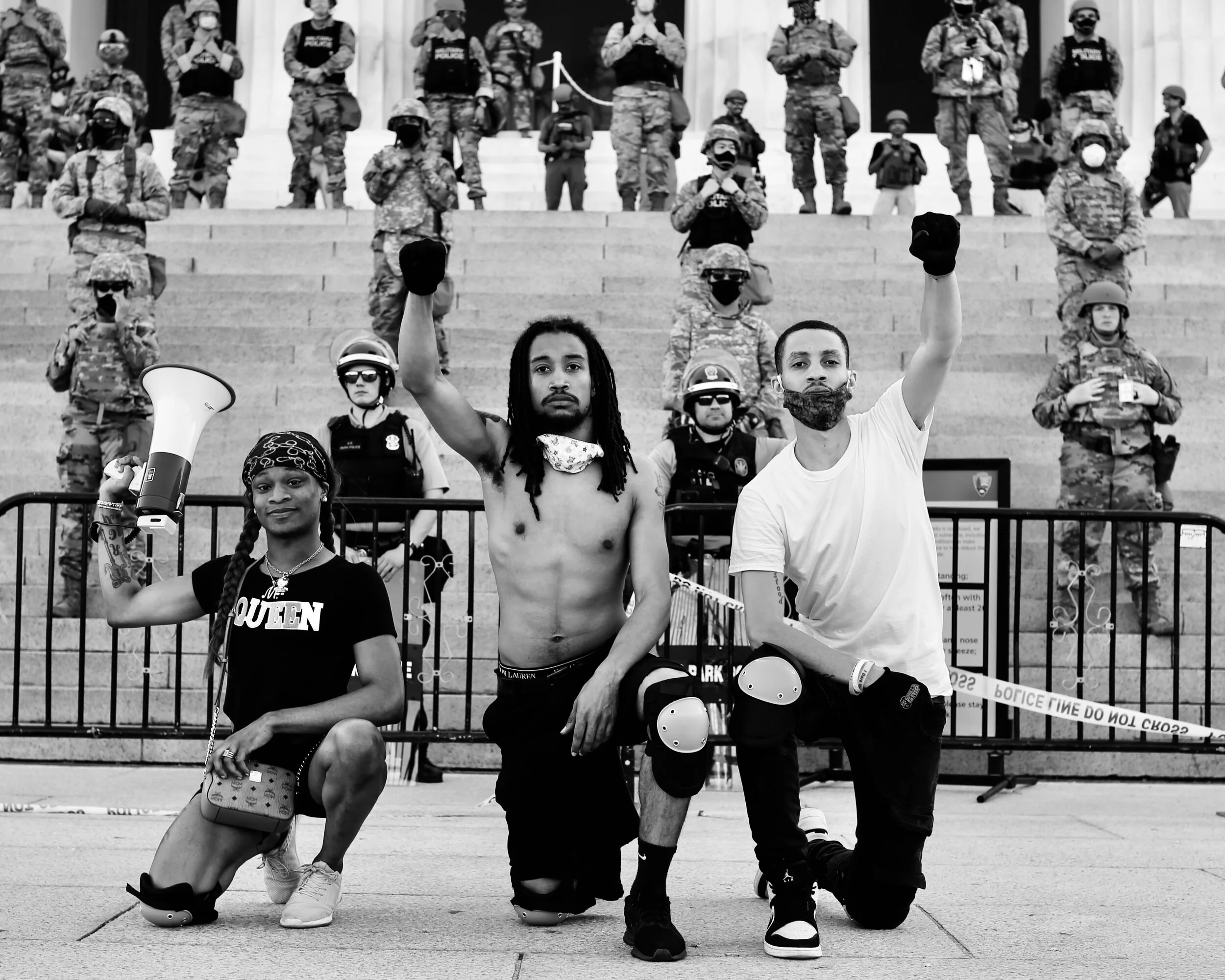

Mingo in front of a crowd at the Lincoln Memorial.

My first encounter with Mingo is as a spectator. Moved by the protests spreading across the country demanding justice for George Floyd, I somewhat impulsively decided to drive to D.C. for a weekend in early June. It’s blazingly hot and bright when I first catch sight of Mingo, who is speaking into a megaphone to a large crowd assembled on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial and beyond. Maybe it’s a trick of the midday sun or maybe it’s the sense of “spirit” that Mingo repeatedly claims to be compelled by—whatever it is, I swear he is almost glowing.

Mingo is wearing a black t-shirt printed with the now-ubiquitous words “Black Lives Matter.” The white letters are formed from an ever-growing list of names, each representing a Black life lost too soon. A homemade purple face mask hangs around his chin and a tattoo on his right forearm brands him as a “Miracle Child.” His speech—in which he recounts marching for Wilson until he was rushed to the hospital outside of Baltimore because of a leg injury—moves me to tears (nothing short of a small miracle in itself).

Later, when I ask him about the inspiration behind his most prominent tattoo, Mingo explains: “It’s because I’m still here—as in living life and breathing despite a lot of life obstacles—and I’m a child of God. It just let’s me know that I'm not done yet.”

Photo: Kristine Jones

MOVED TO MARCH

Not only is he not done, but I’m surprised to learn that Mingo is just getting started. Although, despite his claim that he “doesn’t have much experience” with activism, that’s not entirely true. In addition to the Wilson march, he has always been active in community outreach programs; he works with people who are homeless, and has planned backpack drives for children. But it wasn’t until the George Floyd video sparked a wave of protests that Mingo took to the streets in the more traditional sense.

“I turned the news on and I’m seeing people with signs and it was just an impulse,” Mingo says. “I’m very obedient with God and I felt like he just told me to move.” Running on adrenaline and feeling a pull from deep within, he jumped on the Metro and headed straight to the heart of a spontaneous protest that had sprung up on U Street. “I just planned on being an observer,” Mingo says. “And then, not only am I a part of the march, but I get pushed to the front. It was shocking to me because I had never before in my life done anything like this.”

Photo: Kristine Jones

Nearly two months later, Mingo has led dozens of marches and has been out in the streets almost every day and night since. Hundreds of people, myself included, have followed him over highways, bridges, and rivers; past monuments, buildings, and neighborhoods erected (or devastated) by a system he is hoping he can help change. He has organized candlelight vigils for Davon McNeal, another D.C. child who was shot and killed recently, collected money to buy a basketball hoop for Black Lives Matter Plaza, and continued his outreach efforts with the District’s growing homeless population. The protests may be receiving less and less media attention, but Mingo is not going anywhere.

“The main thing is consistency,” he says. “With this protesting stuff, you’ve gotta be consistent. Yeah, we’ve got some hot days—but they’re still making some messed up laws. Yeah it’s hot, but the police are still killing—they don’t care about the temperature and neither should we. We should be protesting every single day if need be.”

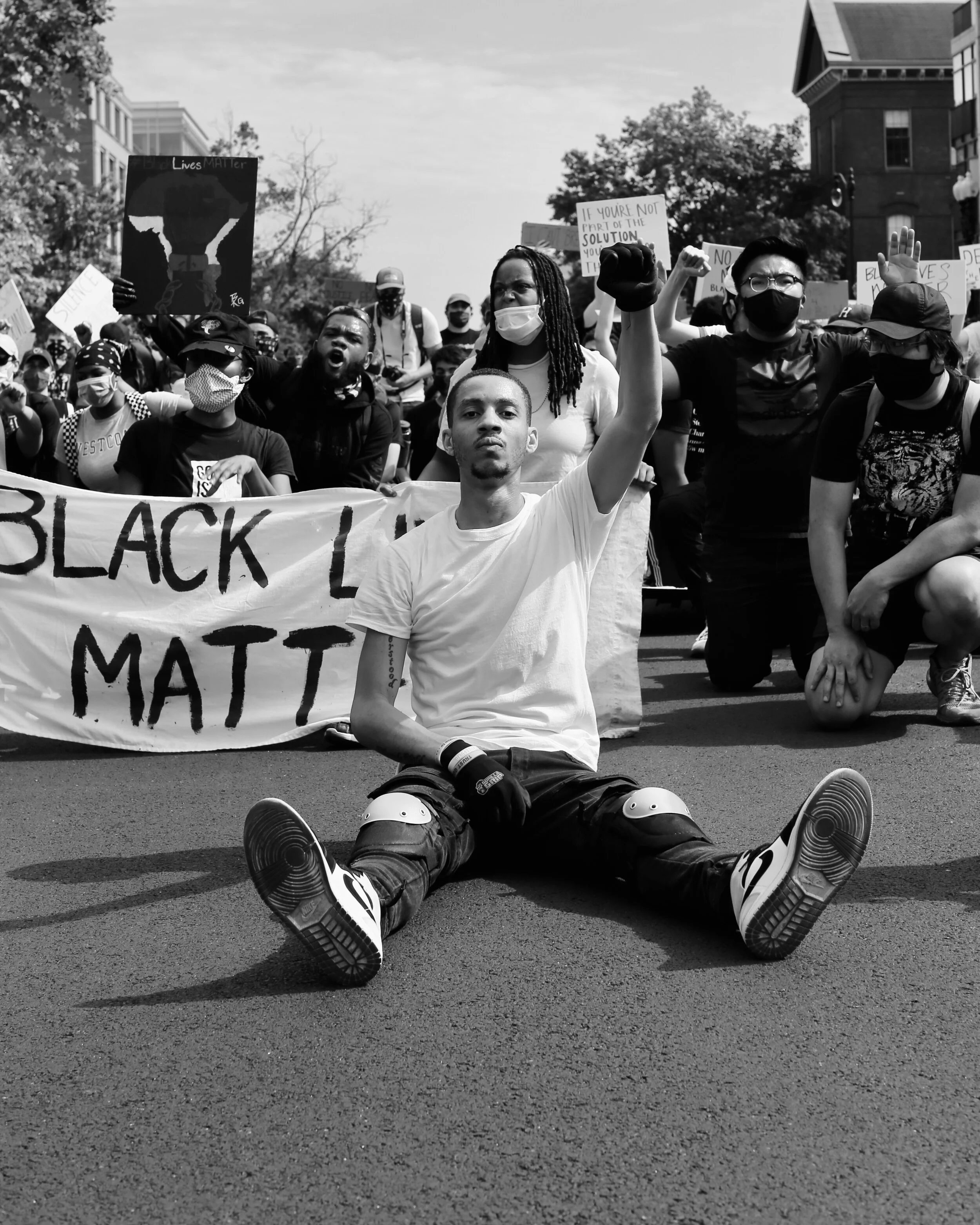

Mingo leading a march for Devon McNeal

Not everyone may be blessed with Mingo’s seemingly bottomless energy, but he repeatedly insists that there is “strength in numbers,” and he’s quick to downplay his individual contributions to the movement. “I don’t want people to get so strung up on me,” Mingo says. “I know I may motivate people but other people have it too. I’m not perfect—I have flaws, I make mistakes all the time.”

Mingo, luckily, has more than a little help from his friends. He formed His Mission Organization with St. Louis native Aaron Covington and others, all of whom he met recently while out protesting. They’ve been planning marches via conference calls, but Mingo isn’t a big fan of turning protests into ticketed or “must-do” events, preferring the type of spur-of-the-moment gatherings that first inspired him to take action. Mingo says he’s also had to be more careful about the routes or actions he suggests—because he’s still surprised to find that (to paraphrase Carole King) where he leads, others will follow. “I joked about shutting down the highway the first night,” Mingo says. “People said ‘So we’re going to do the highway? We’re following you.’”

Despite the well-deserved attention, Mingo says he’s careful not to appear as if he’s “clout chasing,” his term for the type of performative activism that results in an Instagram photo and not much else. “All those people that were here when this first started—where are they now?” he asks. “They only want to come out when there’s an event planned on a Saturday. But we’re still battling every single day.”

Photo: Kristine Jones

While he acknowledges that not everyone can devote themselves wholly to a cause, he views protesting as more of a relay race than a solo sprint. “If I can’t do a march today, then whoever else is a leader—or claims to be—you should be doing a march that day. Then I can pick back up—it should be a rotation. I don’t expect any organizer to do a march every single day but it should be passed on.”

But Mingo knows that it’s not easy to maintain momentum; he even likens the constant stress of protesting to “going to war.” He’s been shot at with rubber bullets, tear gassed, and watched as fellow activists struggled with the debilitating side effects of PTSD. Urged to rest by friends and family members who care deeply about him, Mingo says he’s been more mindful lately of taking time for himself. “But we’re used to working hard,” he says, referring both to his family and his Black ancestors in general. “We’re no stranger to labor. I could go home right now and turn on the news and something else has happened. I’d feel guilty, thinking I should have been out there, I probably could have stopped it. It’s like trying to be a superhero in a way.”

Photo: Kristine Jones

A SENSE OF HOPE

Although he spends most of his time around the two-block-long section of 16th Street NW recently renamed Black Lives Matter (BLM) Plaza, Mingo is skeptical about D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser’s commitment to real, structural change. Just a few weeks after creating a de facto hub for the growing movement, confrontations on the plaza between largely peaceful demonstrators and the police have grown increasingly violent—and occur seemingly at random.

Medical supplies, tents, and food stations have been raided and trashed, t-shirt vendors were banished (and threatened with hefty fines), and depending on the time of day—or officers on duty—something as simple as jaywalking could suddenly be deemed an arrestable offense. “BLM brought people back a sense of hope—which is a good thing,” Mingo says. “But a lot of these people are homeless themselves and they’re still finding ways to give. Having their stuff thrown away? That’s just pure evilness. That’s not how I was raised.”

It may seem like destiny to those that believe in such a thing, but no one is as surprised at how quickly and easily he’s slipped on the proverbial superhero cape than Mingo himself. “Back in high school, I didn’t like bullies or anything that dealt with injustice,” he says. “I just like to stand for what’s right. It’s second nature to me—an impulse.” Although he says he never thought of himself as a leader, now that he’s seen that way by others, he says he’s up to the challenge. “It’s a badge of responsibility if people are putting their faith into marching with me,” Mingo says. “It’s my job to protect them as much as I can.”

Mingo at Black Lives Matter Plaza. | Photo: Kristine Jones

I don’t believe in the idea of ‘God,’ at least not in the traditional sense, but I’ve put my faith fully in Mingo during several marches since I first stood in awe of him at the Lincoln Memorial—and it’s hard to deny that the ‘miracle child’ seems to have been destined to motivate and inspire others.

Mingo’s great-grandfather was a 33rd degree Mason and his dad is a marine veteran. “I have a structured background,” Mingo says. “But I don’t agree with any of it. I’m not a fan of the government because I know that they’re not for us—from the city officials on up. You’ll catch them out here at a march trying to get a photo-op to further their campaign but they’re not really here for the people.”

The women in his family may have assumed less traditional leadership positions—his grandmother works for the Census Bureau and his mother raised Mingo and his siblings as a single mother—but they were no less influential in Mingo’s life. He says supporting women is crucial in maintaining the soul (and shear numbers) of any movement. “Women are already strong by themselves,” Mingo says. “But we have to keep building them up.”

Although he “didn’t worry much as a kid,” Mingo says that when he entered his teens, he came to expect police harassment as a simple fact of life. “We were terrified then but it wasn’t ‘Will we get shot or killed?’ it was more like ‘Ok, we might get beat with a nightstick or something.’ That doesn’t make it any better, but today it’s really out of hand.”

Leading a march through a tunnel.

On July 4th weekend, 11-year-old Devon McNeal went to fetch a phone charger from his apartment complex in Southeast D.C. when he was shot and killed by a stray bullet. A few days later, Mingo worked with McNeal’s family to organize a march from BLM to the Anacostia neighborhood where the boy lived and died. I joined that march, which stretched over several hours and continued well into the night. The group started small but grew along the way—people are drawn to Mingo like a protest Pied Piper, who is not only a compelling speaker, but a magnetic frontman. It’s nearly impossible to not feel something when you’re in his presence; at one point, our small group stopped traffic on a highway and I found myself linking arms with people I had met less than an hour before, in a tense standoff with a line of cars. Mingo, first raised high above his head, paced back and forth, weaving in and out of traffic like a lion in a cage.

When we stopped for a candlelight vigil in front of the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, a larger group joined us and we marched through the neighborhood, shouting “Black kids lives matter,” and calling for information on McNeal’s killers. “It broke my heart,” Mingo says. “At the vigil, a mother was out there with her son. She said ‘My son was terrified because he saw the police lights’ and he told her “Mommy, I don’t want to get shot.’”

Mingo and his daughter, Jaidyn.

A few weeks earlier, Mingo brought his 10-year-old daughter, Jaidyn, to a march he planned for Father’s Day. The more than six-mile, midday march was grueling, but Jaidyn is clearly her father’s daughter. It was her first protest, and she’s already asking to do more—but Mingo is fiercely protective and reluctant to put her in a situation that might turn dangerous. “I felt the atmosphere out on that one but I’m still cautious because in a split second something can happen,” he says. Both of his children currently live in Maryland with their mother, but Mingo says they’re in near-constant contact—and the worry goes both ways. “Jaidyn watches the news—she knows what’s going on—and she’s constantly checking up on me,” he says.

Last year, Mingo himself was arrested in Maryland and spent five days in 24-hour lockdown—for something he didn’t do. Months later, he is still paying down his debt to a bail bondsman for a crime that everyone—including the judge and attorneys—agreed he never committed. Still, Mingo says, “It could be worse.” His own mom agrees. When I ask how his family views his recent foray into activism, Mingo says, “They’re proud and happy.” But his mother has mixed emotions. “She’s happy, she’s proud—but also terrified,” he says. “She always says, ‘I don’t want you to be another hashtag.’”

Leading a Father’s Day march through the tunnel.

PEACEFUL PROTESTS

Maybe it’s God or maybe it’s just luck, but thankfully Mingo has so far managed to avoid the grim fate of so many people like him, whose only “crime” is to be Black in America. Despite the constant awareness that comes from living within a system that is actively working against you, Mingo has shown remarkable restraint in his interactions with police officers. “I don’t have a beef with the police, personally,” he says. “In general I don’t like them, but if the officer is showing me respect, I'm going to treat him with respect back. But if that officer pulls out their gun or tear gas then yeah, we’re gonna have a problem because now you’re trying to instill fear in me. I’m unarmed. There’s no reason for you to do any of that.”

While some may argue that the act of protesting can never truly be peaceful, Mingo’s philosophy on non-violence is backed by a long history punctuated by leaders to which he has inevitably drawn comparisons. But even Mingo admits that a commitment to non-violence has its limits. “If you have a bully that keeps bothering you, keeps poking at you, you’re soon not going to be peaceful anymore,” he says. “That’s what we’re dealing with right now.”

Mingo leading the Father’s Day march with his daughter Jaidyn.

The star-spangled elephant in the room—or the “bully” to which Mingo repeatedly refers—is, of course, Donald Trump. Mingo sees an obvious link between the Mayor Bowser and Trump standoff, and the so-called riots and looting that occurred early in June: “When the head is out of order, so does the body follow,” Mingo says. “People in high positions—law makers, specifically—if they’re not respecting each other or the laws that they are making, how do they expect the people to respect them? This is why you’re getting riots and looting. People are not doing it for no reason. We’re fed up.”

Mingo recently attempted to keep the peace at Lincoln Park when a rally concerning the fate of the park’s polarizing Emancipation Memorial quickly devolved into a shouting match. Although he usually finds himself behind the megaphone, Mingo tries to encourage conversations over confrontations, whenever possible: “As the saying goes, ‘God gave us two ears and one mouth so we would listen more and speak less.’” Incidentally, Mingo is on the side of those calling for the statue’s removal, but he’s wary of anyone who wants to do it in a destructive way—especially after Trump issued an Executive Order calling for the extreme punishment of anyone caught doing so. “Yes, it needs to come down,” Mingo says. “But the right way.”

Photo: Kristine Jones

UNCONDITIONAL FAITH

A few weeks after I first hear Mingo speak, we’re once again at the Lincoln Memorial. The day is just as hot and sunny, but this time we’re sitting in the comfortable shadows of the monument’s massive marble columns—and in the figurative shadows of everyone who has stood on the historic steps nearby to give similarly stirring speeches. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech just a few hundred feet from where we’re sitting. But it’s another speaker from the 1963 March on Washington who is on my mind while I chat with Mingo. John Lewis, who visited BLM Plaza just a few weeks before he died on July 17, once said, “Our struggle is a struggle to redeem the soul of America. It’s not a struggle that lasts for a few days, a few weeks, a few months, or a few years. It is the struggle of a lifetime, more than one lifetime.”

Mingo—who cites Lewis, along with Malcolm X, Black Panther co-founder Huey P. Newton, and the rapper T. I. as important influences—also understands that the fight for justice has no beginning or end. “A lot of people are trying to put time limits or days on it saying ‘We’re going to end it when …’ but I say, ‘No, what we’re doing it for has not been accomplished yet. I’m 30 now and I could look up and be 50 and still be out here marching.”

If the ‘miracle child’ tattoo doesn’t make it obvious, Mingo is undeniably a man of faith. He attended a Bible college in Lancaster, Pennsylvania and studied youth pastoral ministry. He says he does a lot of writing and thinking before his speeches, but in the end, he simply let’s the spirit flow through him. “I ask God to ‘put the words in my mouth that I may not have or may not know’ and then I just face the day,” Mingo says. “He hasn’t failed me yet. I’m just a vessel that God chose to use. I don’t want him to have to take his hands off my life and say ‘You’re out here for the wrong reasons so I’m going to let the enemy have his way.’ That’s probably my only fear in life. I don’t want to face God with that.”

Photo: Kristine Jones

I can attest that listening to Mingo speak is nothing short of a spiritual experience, but unlike the mega-church from which he recently severed ties, all are welcome to worship beneath the powerful, perpetually-raised fist of Mingo. “I’m for any and all people who are on the right side,” Mingo says. “I don’t care about your sexuality, your race, your religious beliefs. When God looks at everybody, he looks at the intentions of the heart. That’s it. I’ve never known a heart to be black or white. A heart’s a heart.”

It can be difficult to maintain one’s faith in normal times, and no one would fault Mingo for buckling under the overlapping sorrows of 2020. But faith is more important now than ever, he says, and should never be conditional. “Faith is probably when you’re scared the most. Walk by faith, not by sight. We’re more scared of things we don’t know. We don’t know how long this will last. Evil never wins—it might feel like it is winning right now. But it never wins because God always has the last say so. God made life simple for us. Man made life complicated.”

Mingo, who usually wears a t-shirt, jeans, immaculate sneakers, and a rotating selection of statement face masks, is in many ways, a perfect representation of our current reality. He lost his job due to the pandemic, and is about to start working nights at an Amazon warehouse. Once again, Mingo has every reason to be angry and despondent; he thinks it’s no accident that people have reached a breaking point now—and he says that unfortunately, sometimes it takes a personal tragedy to light a fire under people who wouldn’t have otherwise cared. “God is exposing the truth on a lot of things that have been kicked under the rug,” Mingo says. “It’s like the rug has been lifted up now and a lot of things are coming out now. People are losing jobs, they’re out of work. The pandemic has everyone’s attention. It really exposed people’s insecurities in their own lives.”

He knows that the issues he’s fighting for are not new, but says that people do seem to be more receptive to having more meaningful conversations about them. “These are the same problems we’ve been having—police killing did not just start—but it hit differently with the pandemic,” Mingo says. “People can’t claim anymore that they’re so busy that they’re not paying attention. You’re not busy, it’s in your face, so what are you going to do? You could be next.”

Photo: Kristine Jones

BLACK LIVES MATTER

For Mingo, simply acknowledging that Black lives matter is the starting gun—not the finish line. “It’s not even about race anymore,” he says. “It’s about what’s right and what’s wrong. I’ve seen some white people, Spanish-speaking people, LGBTQ people going hard for us—because we’re all dealing with the same thing. I feel like all people should have a voice.”

While being a Black man in the U.S. comes with its own unique set of challenges, Mingo recognizes that he has privileges as well—but, as MLK Jr. said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

“I don’t know how it feels to be transgender,” Mingo says. “But I think I know how it feels in general because they feel mistreated. Immigrants came over here trying to create a better life for their family and now they’re trying to send them back over the border. I don’t know how that feels but I may have an idea because they feel mistreated. Black people are being killed by the police. I don’t know how that feels because I’m not dead—thank God—but that’s the common thread. Feeling mistreated.”

Mingo stops short of using the now-incendiary phrase “All Lives Matter,” but he does insist, “I’m here for everybody. Yes Black lives do matter. But at the same time everybody matters.”

While I agree with Mingo, I also can’t help but think that not everybody can—or should—follow exactly in his sneaker-clad footsteps. But that’s the good thing about mass movements, there’s a place for everyone—and clearly Mingo belongs at the front of the crowd.

Mingo during the Devon McNeal march.

Mingo, who also has a budding music career, may always be in constant conflict with his impulse to lead and his fear that his ego may unintentionally eclipse his higher purpose. But he’s actively working to make sure he remains focused and in service of others, and, of course, God. “I don’t think I’m bigger than anybody—I don’t think I’m doing a better job than anybody,” he says. “I like coming together with others. Maybe you can give me a different outlook on something that I didn’t think about. But you gotta understand, you’re dealing with the streets and the streets are going to call your bluff. If you’re doing it for the wrong reasons, the mask eventually falls off. It may not fall off in a week or two weeks—it may take a month—but eventually people are going to see.”

What I see in the time I’ve spent marching and talking with Mingo is nothing short of complete sincerity—and I try to assure him that his fears of being seen as a “clout chaser” are more than unfounded. But he admits that his inability to properly finish the Makiyah Wilson march might still be motivating him to go extra hard for other families mourning similar losses of their own.

“Maybe it’s a self pride issue,” Mingo says. “I didn’t get to finish [the Wilson march] out the way I wanted to. So I’m looking to finish this out—however long it takes. I don’t half ass anything. If I’m going to do it, I’m going to do it all the way. I know what I signed up for. I know I can’t save the world but I’m going to try.”