Abandoned Psychiatric Hospital

I definitely feel as if I’ve missed the glory days of exploring abandoned psychiatric hospitals. While psychiatric hospitals still exist to some extent today, the widespread use of medication to treat mental health issues was the final blow to many hospitals that had already seen a steady decline in their populations and resources over the years. This particular hospital, located in upstate New York, opened in 1924 and closed in 1994.

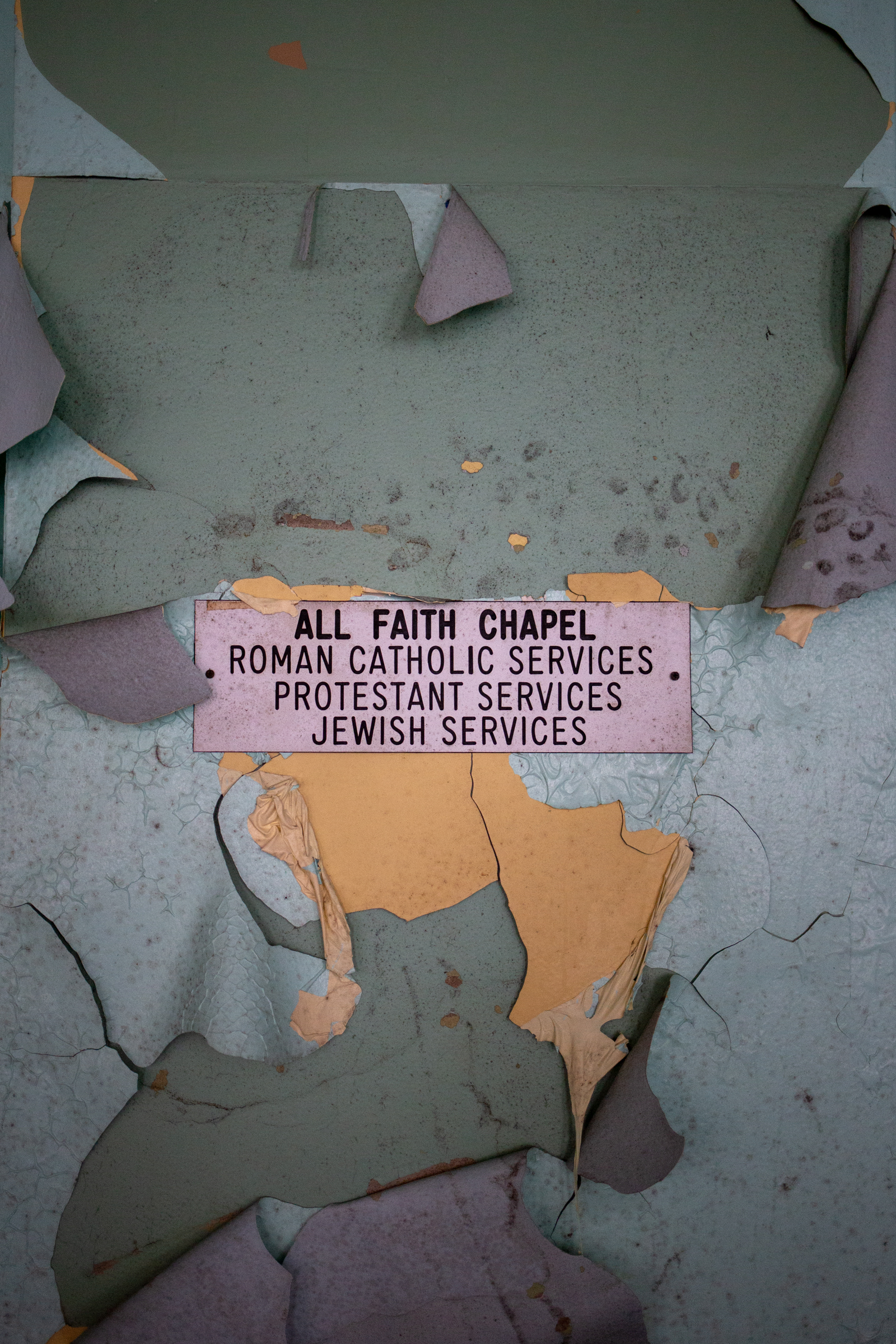

The site was originally planned as a penitentiary, but nearby residents complained, so the buildings were repurposed as a psychiatric hospital. I’m not exactly sure how that swap pacified concerned neighbors, but the hospital operated for 70 years before closing due to budget cuts. The property was sold and several plans for redevelopment have been made throughout the years, but most of the buildings still sit abandoned.

The unique thing about exploring abandoned psych hospitals is that—like prisons—they were built specifically to keep their residents inside. The windows are barred, the heavy metal doors often lack windows and if you do manage to get inside, good luck keeping track of where you are or finding your way back to where you started. I joked that we needed to leave a trail of breadcrumbs, but it really is a small miracle that we found our way out without them (or accurate GPS readings).

The 900-acre campus once contained nearly 80 buildings, and included a golf course, baseball field and dairy farm. In the facility’s heyday, a staff of 5,000 cared for 5,000 residents. Experimental treatments practiced in this hospital included insulin- and electro-shock therapies and this was the place to get a frontal lobotomy in New York state, most likely administered by the infamous ice pick lobotomist—and owner of the Lobotomobile—Walter Freeman.

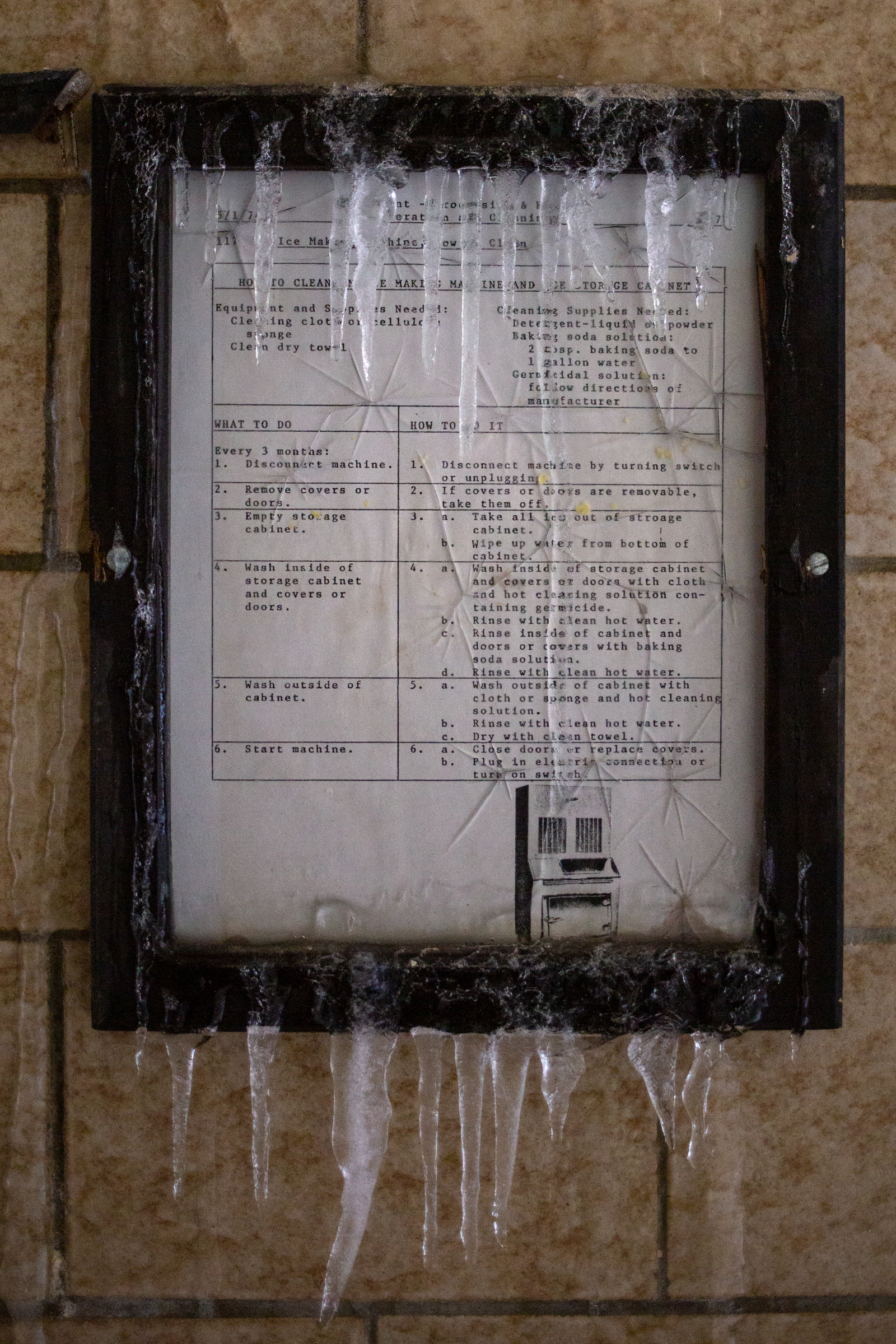

The hospital was built in the Kirkbride style, a plan devised to allow the patients fresh air and sunlight. Buildings are separated by courtyards and connected by partially underground tunnels, so once you’re in one building you can access several others from a central spoke. The central building contained a large kitchen (which was coated in a thick layer of ice, including the operating instructions for … the ice machine) and several dining areas.

Common areas are always my favorite to explore because they always seem to have more stuff—and hints of life—left in them. By far the best part of this hospital is its bowling alley, a common feature in psychiatric hospitals, but a surprise find nonetheless. In addition to being relatively graffiti-free, this two-lane alley had adequate light, which is rare—usually recreation areas are relegated to dark basements. The whimsical murals and ball left mid-roll makes the space feel as if it was just a few moments—instead of a quarter century—away from having been enjoyed by patients.