Gravesend Cemetery

Gravesend, founded in 1643, was one of the original towns in the Dutch colony New Netherland, and one of the six original towns in Kings County. Founded by Lady Deborah Moody, the original English settlement included 39 other people. Moody was the first woman to found a township in the European colonies (what a total badass woman in 1643!). Gravesend wasn't incorporated into Brooklyn until 1894, and then became part of New York City when Brooklyn voted to join with the four other boroughs in 1898.

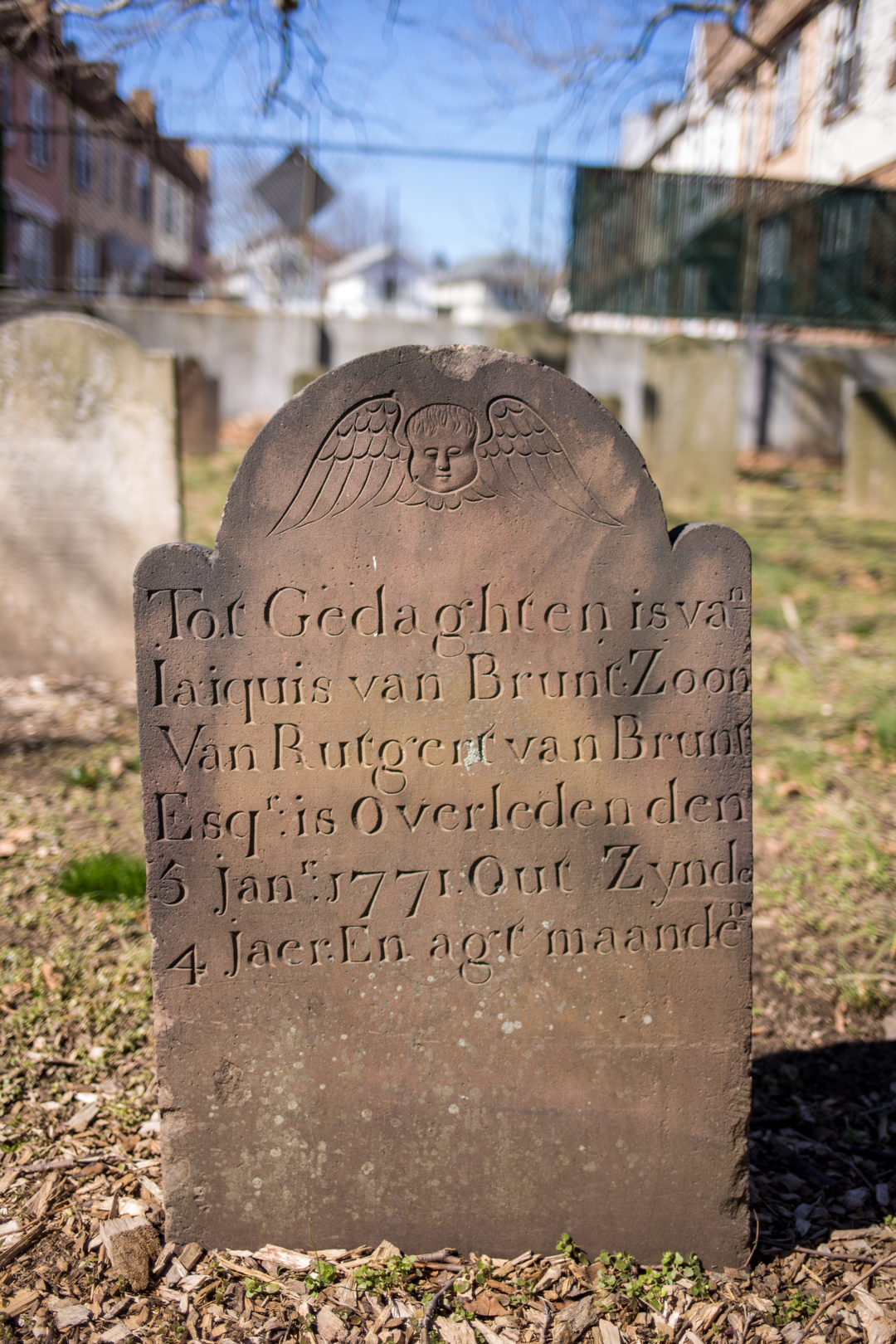

Gravesend Cemetery was founded around 1650, although the earliest surviving marker—a crudely carved fieldstone—dates from 1724. Early burials where likely Quakers or others who marked their graves with simple stones or wooden markers that haven't survived. The earliest traditional tombstones still visible are Dutch stones with intricately carved winged cherubs from the 1760s/70s.

I first went to Gravesend Cemetery back in 2014, and was disappointed to find the cemetery locked. There were no posted hours (just as sign that said open by appointment only), but I hoped that I would one day find a way to get inside of the historic grounds. That day finally came on Sunday, when my mom and I took a free tour offered by the New York City Urban Park Rangers.

Tours of the cemetery are only given once a year and online registration had already closed by the time I found the event listing. I contacted NYCParks via Twitter to inquire about the event, and they suggested that I call the Urban Park Rangers. I temporarily overcame my phone phobia and spoke to a very nice woman who informed me that there was still space available. We were added to the list and the moral of this story is that obscure cemetery tours on chilly winter days aren't exactly a hot ticket—and that I can be persuaded to talk to an actual human on the phone if it means that I might get into a normally off-limits cemetery.

If I have the choice of a guided tour or wandering on my own, I'll always pick the latter but this tour was a good combination of both. Our park ranger was very knowledgeable and I never felt rushed. We also heard a few stories about notable burials that we would have never been able to infer just from looking at the stones themselves, which certainly makes the case for taking a tour if it's an option.

Barnadus and Sarah Ryder were brought to our attention, a husband and wife who died 34 years apart—but both on October 29th. We were also directed to find the one marker not made of stone, a blueish zinc head"stone"—I've seen these in cemeteries before, but I didn't know that all zinc markers were produced from a single company in Connecticut from about 1870 to 1912.

Viola Jackson was a black woman working as a maid when her dress caught fire—either from a candle or the oven—and she died tragically when she was just 22. She is buried in the cemetery, but along the southwest edge with other African Americans of that time—Gravesend's own interpretation of "separate but equal."

Jacob and Barnadus Ryder, whose stones are next to each other, died just ten days apart. The father and son didn't die from a shared illness, but rather from a murder-suicide that may have been Gravesend's first. Jacob Ryder, a farmer, cut the throat of his two-year-old son and then cut his own. His wife was in the field milking cows at the time, and although Jacob survived, he died ten days later from the self-inflicted wound. It was later revealed that Jacob had written a letter to his father claiming that he “imagined he heard a voice commanding him to execute the deed.”