Valley of the Kings

Most people have heard of the Valley of the Kings in relation to its most famous resident, King Tutankhamun, whose nearly-intact tomb was discovered by Howard Carter on November 4, 1922. The valley contains 63 known tombs, and 18 are open to the public on a rotating basis.

The Valley, located on the west bank of the Nile across from Luxor, was used for burials from approximately 1539 to 1075 BCE. The name is a bit of a misnomer because in addition to Pharaohs, the valley is also the final resting place of nobles, wives and children—only about 20 of the tombs actually contained the remains of kings.

The Valley of the Kings was our first stop after flying to Luxor, and we arrived just after noon (yes, it was very, very hot). The Valley has been a popular tourism destination since antiquity and the tombs contain more than 2,000 instances of graffiti. Members of Napoleon’s expedition visited the Valley in 1799, and Belzoni—former circus strongman and my favorite Egyptian explorer—discovered several tombs in the early 1800s.

Tickets for the Valley of the Kings allow you to visit three tombs of your choice, but separate tickets must be purchased to enter the tomb of Tutankhamun. Purchasing yet another separate photo ticket will allow you take photos inside of some of the tombs, but photography is prohibited completely in others, like KV62 (Tut’s tomb). Carter’s discovery was such a big deal because it was the first time a royal tomb had been found that still contained an intact burial. The tomb had actually been robbed several times in antiquity, but a large amount of funerary treasures still remained in the tomb.

Thieves never discovered the young king’s mummy and it is now displayed in his tomb adjacent to his gilded wooden coffin which lays inside of his sandstone sarcophagus. Aside from a few paintings, there is nothing else to see inside of the small tomb—the rest of his treasures are on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo and the entire collection is in the process of being moved into the still under-construction Grand Egyptian Museum.

I don’t want to sound bratty and say that I was disappointed with King Tut’s tomb (I was), but I was also pleasantly surprised by the beauty of the other tombs that we toured. The Valley was our first experience with richly decorated tombs, and while they’re all different, they’re all spectacular in their own ways. It’s a shame that most were stripped of their treasures, but I’m glad that the beautiful interiors haven’t remained hidden forever, as originally intended.

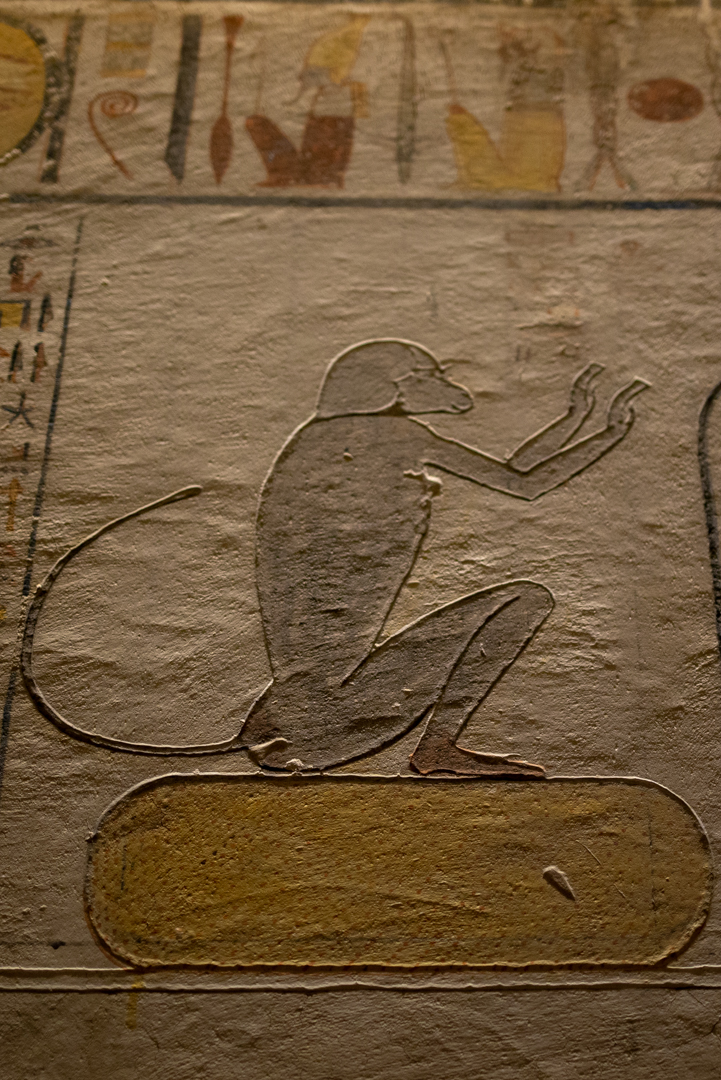

KV2, the tomb of Rameses IV, has been open since antiquity but is somehow still covered in colorful carvings and reliefs of scenes from the following funerary texts: Litany of Ra, Book of Caverns, Book of the Dead, Book of Amduat and the Book of the Heavens.

One of the things I was most blown away by in Egypt was the meticulous planning of the Ancient Egyptians, and there were two plans discovered for the layout of KV2—one on papyrus and one inscribed on a slab of limestone. The tomb has three corridors followed by a large chamber and the burial chamber. Past the burial chamber is a narrow corridor and three side chambers. The successors of Rameses III (there were at least eleven Pharaohs that took the name Rameses) constructed and decorated their tombs in a similar style.

KV6 was the final resting place of the 20th-dynasty Pharaoh Rameses IX. There are indications that the tomb was not finished at the time of Rameses's death and that it was rushed to completion. Graffiti left by Roman and Coptic tourists can be seen on the tomb’s walls.

The most dazzling of all the tombs we saw in the Valley of the Kings, however, belonged to Seti I. KV17 was discovered in 1817 by Belzoni, and it also requires a separate ticket for entry. If you only have time to see one tomb in the Valley, I would direct you to this one, which contains beautifully preserved decorations in all but two of its eleven chambers and side rooms. Work on the tomb was abandoned upon the death of Seti, and although photography wasn’t allowed I couldn’t resist snapping a few photos of the unfinished drawings that offer a rare glimpse into the Ancient Egyptian’s artistic process.

Bonus Mummy Content:

In 1881, a tomb-robber discovered a tomb at Deir el-Bahri containing the mummies and funeral equipment of more than 50 kings, queens, and other royalty, including mummies that have been identified as Rameses IX and Seti I. A separate cache was discovered in the Valley of the Kings, containing more than ten mummies, one of which was identified as Rameses IV. The only mummy still in his original tomb is King Tut’s, but the others can be viewed at the Egyptian Museum (no photos allowed in the Royal Mummy rooms) and in the Luxor Museum.

One of the mummies currently at the Luxor Museum took a rather circuitous path to get there. A Canadian doctor purchased one of the mummies from the Deir el-Bahri cache and it soon ended up at the Niagara Falls Museum. The museum exhibited curiosities (my kind of museum) and its collections traveled between Canada and New York before it closed in 1999.

In the 1980's, the mummy was tentatively identified by a German Egyptologist as Rameses I, and when the museum closed it was sold to the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University in Atlanta. The mummy was studied and identified as royal—its arms were crossed right over left on its chest and radiocarbon dating placed the mummy from sometime between 1570 to 1070 BCE. In 2004, it was returned to Egypt and is now resting much closer to its original home, just across the Nile in the Luxor Museum. The Rameses I designation remains controversial, and the placard in Luxor simply identifies it as a Royal Mummy.

💀 Happy Halloween! 🎃