St. Michael's Cemetery: Portraits

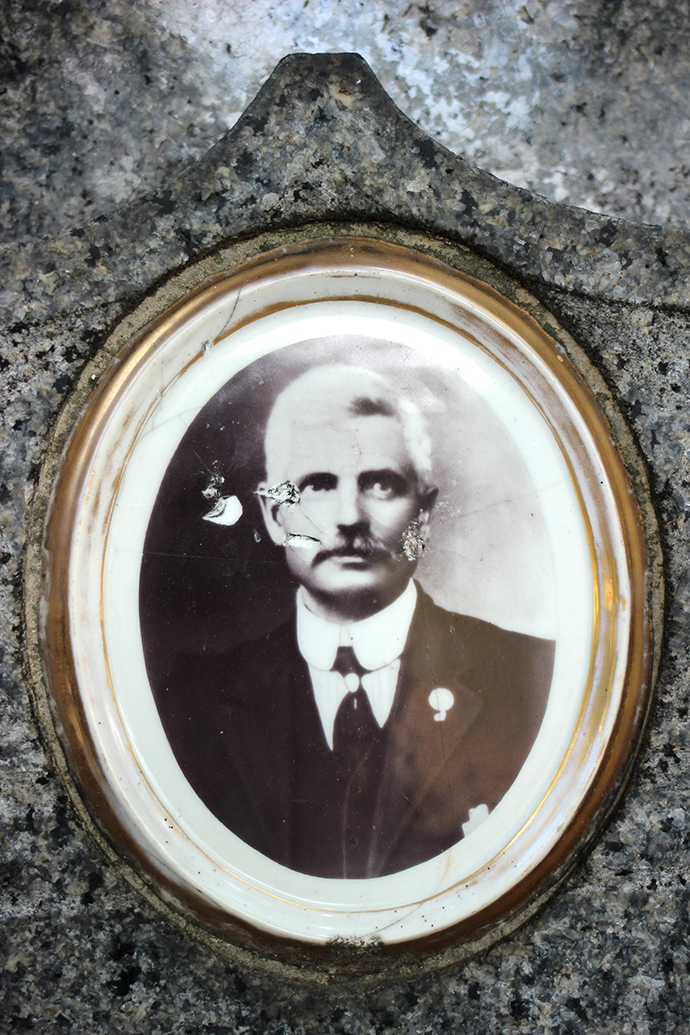

I've seen ceramic portraits on headstones before, but—in addition to its plethora of headless statues—St. Michael's Cemetery in Queens has some really wonderful ones. In 1854, two French photographers figured out a way to transfer a photograph onto porcelain or enamel and the process quickly caught on to include memorial portraiture affixed on tombstones. By the beginning of 1900, these portraits were becoming so popular that you could even buy them from the Montgomery Wards & Company Monuments catalog.

Ceramic portraits pop up in most of the cemeteries I've visited, and it's still a popular tradition on modern-day headstones. They seemed especially popular in Hartsdale, America's first pet cemetery, which makes sense and proves that long before Instagram, people were obsessed with photos of their pets. Of course it's the old, black-and-white ones that I love, and almost all of the ones I found had beautiful gold-painted detailing or a frame of some sort—the copper wreath and bow is one of my favorites.

Unfortunately a lot of the early ceramic portraits that you come across are damaged—chipped, broken or faded away completely. Today's portraits are made utilizing a more fade-resistant process, and it's sad that so many of them are already lost. Sure the portraits are a bit creepy—eyes staring at you from beyond the grave for all of eternity—but I happen to think that they're also sweet. They're infinitely preferable to the modern day scourge that is laser-etched-portraiture, and they humanize what are often cold and impersonal stones. They're proof that these people once existed and lived lives as we all do, for better or worse—albeit in much fancier clothes.